Introduction

The study of the selected area, located between Solfagnano and Villa Pitignano (Perugia), is characterised by the integration of relatively recent technologies into the traditional methodology of topographic survey (Cambi and Terrenato, 1994). This contribution is intended as a preliminary study, given the intrinsic complexity of territorial research. The aim was to highlight the archaeological value of a lesser-known landscape 1 by analysing the territory’s high archaeological potential, settlement dynamics, and past human-environment interactions. By its own nature, this territory acts as a connective space between different cultural spheres of the region, thanks to the Tiber River flowing through it.

The study area

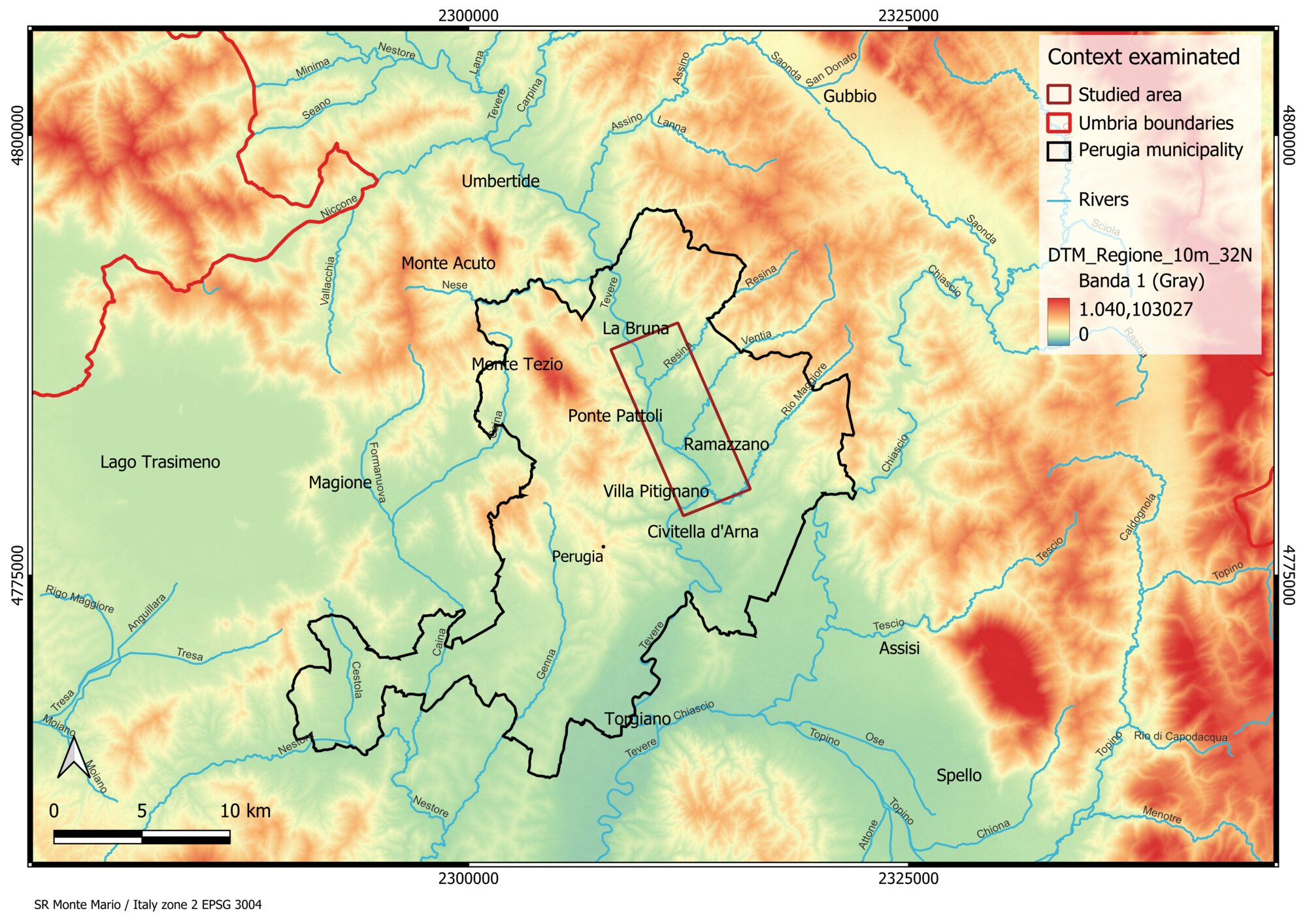

The geographical area here examined (ca. 40km²) is located within the northeast sector of the territory of Perugia and along the Upper Tiber Valley , between the Umbrian Valley to the southeast and the Middle Tiber Valley South to the southwest (Figure. 1). The boundaries of the area selected for this study were identified by considering the modern administrative limits of the municipality, the geomorphological features of the territory, and the course of the Tiber River (Kolendo 1969; Cifani 2003, 23). The territorial context examined here is linked to a broader landscape framework that characterises the north and central Umbrian and southeastern Tuscan landscape adjacent to the central hilly belt and the mountainous areas. In general, this territory is a typical example of the physical landscape of northern Umbria, and it is characterised by narrow plains with recent or ancient alluvial features and hilly stratifications. The geological history of the territory – which is related to the more complex geological evolution of the region itself – has contributed to the development of a uniform and homogeneous geomorphological conformation (Gregori 2006).

Method

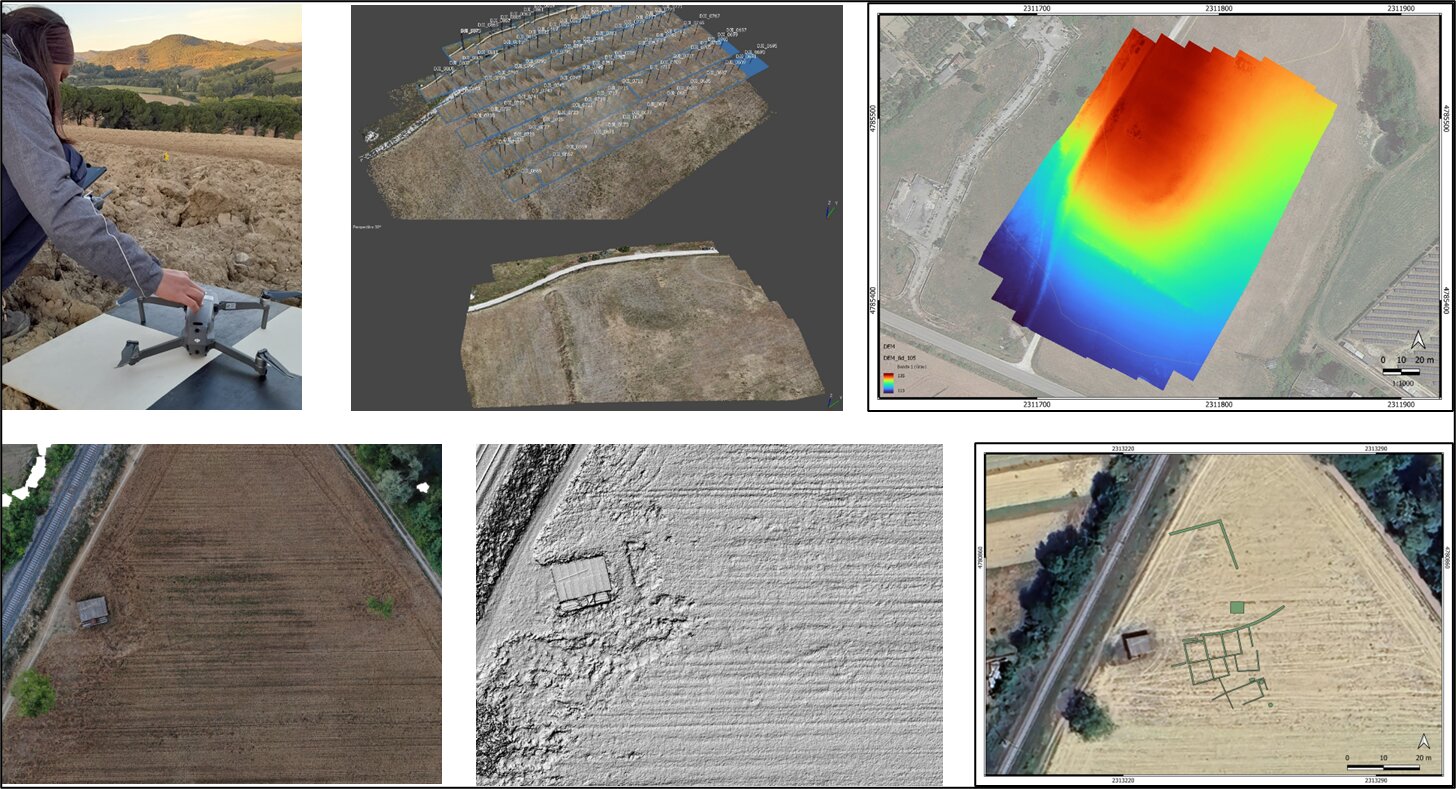

The method adopted in this study is based on a plurality of theoretical and practical elements, paying particular attention to the different scales of detail (Campana 2015; Campana 2018). The approach is structured in three tasks. The first task involved the preliminary study of environmental, geographical, geological and geomorphological features, as well as the collection of published historical, historiographical and archaeological documentation. The second task involved data collection and its organisation in the GIS database (QGIS), thus creating graphic and tabular datasets (Campana and Forte 2017). Preliminary analyses include the identification and interpretation of anomalies through satellite images and orthophotos. Fieldwork activities were carried out using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and a mobile GIS, i.e. QField for geo-referencing data collection in real-time (Montagnetti and Guarino 2020; Mandorlo 2024). During the summer season, in June and September 2021, aerial reconnaissance was performed using a UAV (Mavic 2 Pro DJI). The application of UAV made it possible to generate 3D models, orthophotos and Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), and later, to interpret the anomalies highlighted (Mandorlo 2024, 6-7; Figure. 2).

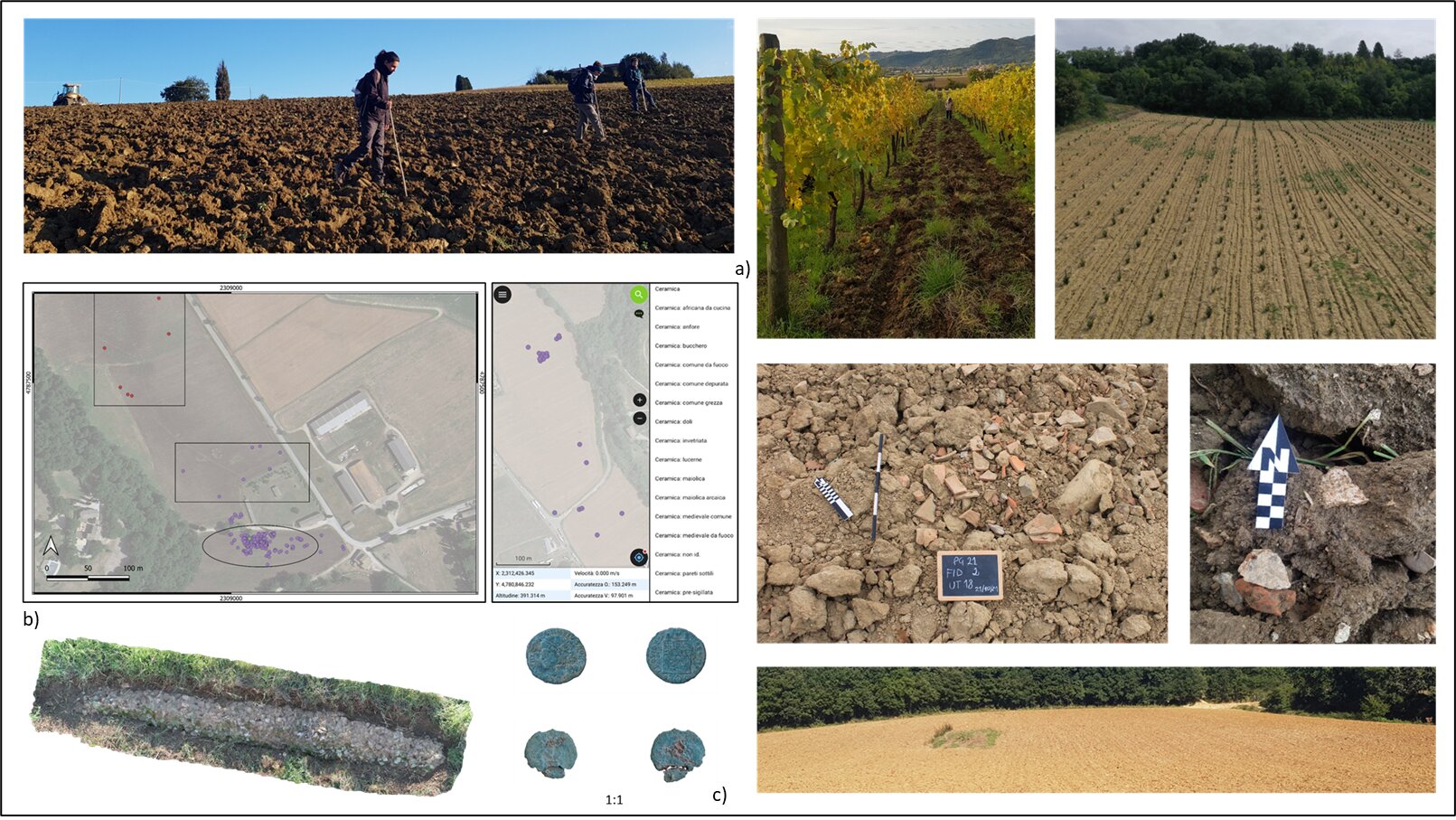

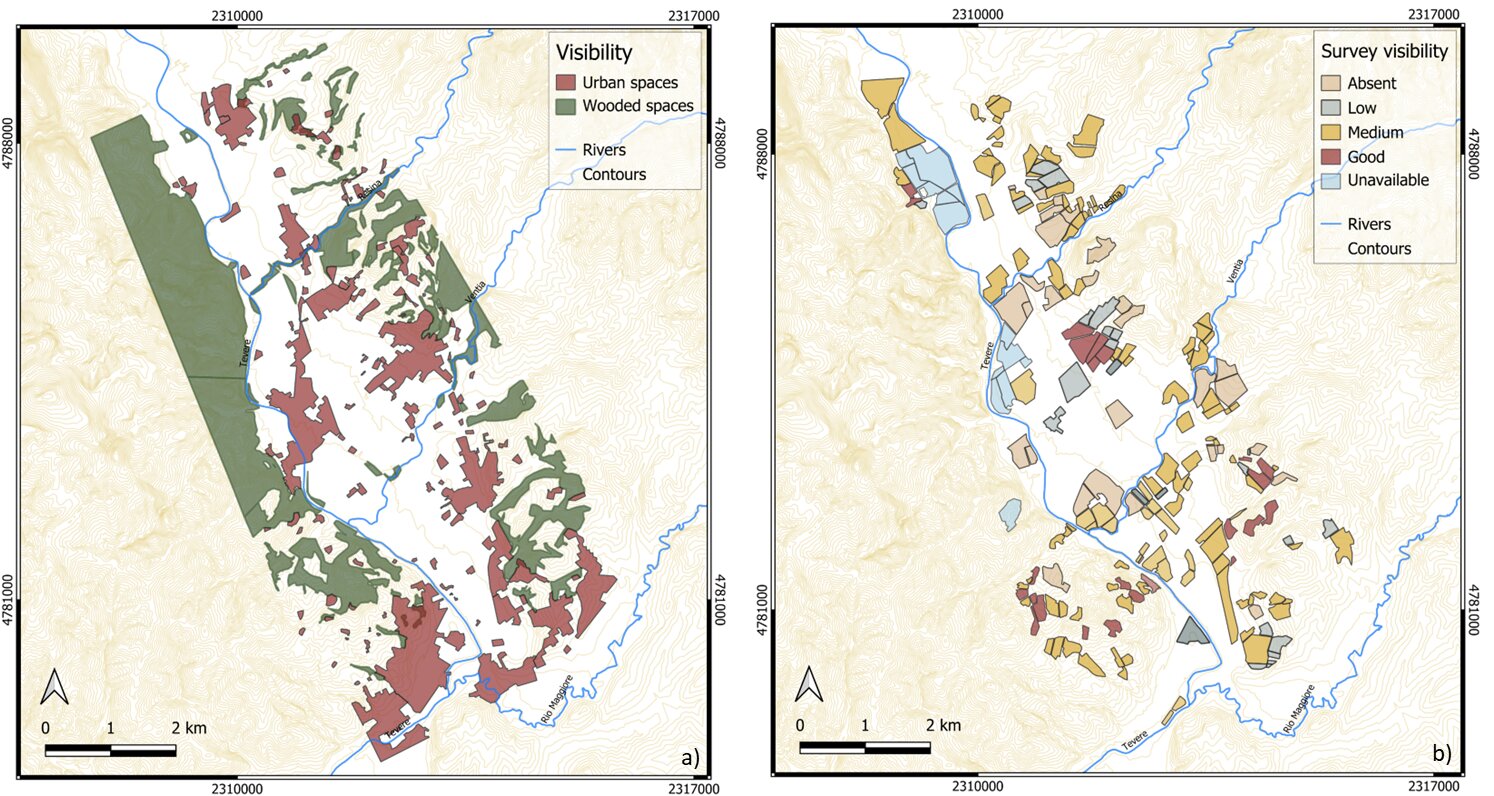

QField was used to geo-reference both internal (“intra-site”) and external (“off-site”) material concentrations (Belvedere 2010, 33), and for the data related to areas where the collected fragments may be considered as indicators of past human activities in the territory, the so-called “background noise” (Cirelli 2006, 170-172; Attema et al . 2020) (Figure. 3 a-b). The survey activity was intensive but not repetitive, with few instances of repeated reconnaissance. Intra-site and off-site fragments played a key role in comparing correlations between off-site and holes, which is crucial for understanding the analytical framework (Cirelli 2006, 171) . QField was used to create virtual grids at fixed intervals. These grids (5x5 m) were inspected by teams of 4-5 people per shift in order to achieve systematic area coverage. When considerable material concentrations were identified, grids were resized for more detailed sampling down to 2x2 m. For low-density concentrations, individual material fragments where recorded as points, while for large concentrations with high volume and density of fragments, sampling strategies were used. The sampling process was influenced by various factors including time and resource constraints as well as the proven effectiveness of the sampling methods in some studies (Terrenato 2000; Cirelli, 2006). Thanks to the tracking function offered by QField, it is possible to clearly define the boundaries of single concentrations. The geomorphological features of these areas, mostly characterised by alluvial and colluvial deposits, display a coherent archaeological pattern influenced by shared agricultural practices (Saggioro 2003, 533). Intensive ploughing in these zones has led to the destruction of buried archaeological remains. The low plain areas with thick alluvial deposits have better preserved the archaeological record. Approximately 18% of the area (46 km²) was unsuitable for investigation due to residential, industrial and infrastructural coverage and 23% is forest covered (Figure. 4a); the remaining area consists of 42% ploughed fields, 9% overgrown areas, and 8% permanent crop (59% of 46 km²). About 10 km² of the remaining area was surveyed (Figure. 4b) between October 2020 and September/October 2021.The third task included reorganisation of the collected data in a GIS database and the study of the material recovered during the survey activities. Each piece of information underwent critical elaboration, and QGIS facilitated the production of precise distribution maps of the evidence. Field activities allowed identification of a considerable amount of data relevant to periods ranging from Prehistory to the Middle Ages 2 .

The approach adopted for the creation of the “Topographic Units” is based on the use of the main interpretative categories outlined during the Carta Archeologica della Provincia di Siena ( see Valenti 1995, 35; Valenti 1999, 53; Campana 2001, 70), which are consistent with the guidelines provided by the ICCD ( Istituto Centrale del Catalogo e Documentazione ; see Mancinelli and Imperatori 2020), and also adopted by the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the production of the Archaeological Map of Umbria. In summary, the interpretative categories used in this research, which define the identified Topographic Units, are frequentation, sporadic, earth house with brick cover (as a building type), farm, and villa .Population diachrony: settlement and socioeconomic models

4.1 Prehistory and Protohistory

Evidence provided by the survey data is scarce regarding the Prehistoric period, and evidence for the Protohistoric period is completely absent. In general, these data fit in with the broader regional framework, which provides some sporadic evidence for the territories bordering Perugia (Moroni et al. 2011, 173). The first documentary evidence of human presence in this territory - mainly attested by lithic artifacts collected by Giuseppe Bellucci between the late 19th and early 20th centuries - dates back to the Lower Palaeolithic (Bellucci 1915). Most of these contexts are distributed near Lake Trasimeno, at the confluence of the Tiber and Chiascio rivers, and in the southern suburb of Perugia (De Angelis et al. 2014). In the northern and northeastern areas of the studied territory, surveys and stratigraphic excavations revealed a complex pre-Protohistoric settlement network along the northern Tiber Valley at the Umbrian-Tuscan border between Città di Castello and Sansepolcro (Lanfredini and Benvenuti 2010, 1-8), and in the territory of Gubbio (Malone and Stoddart 1994).

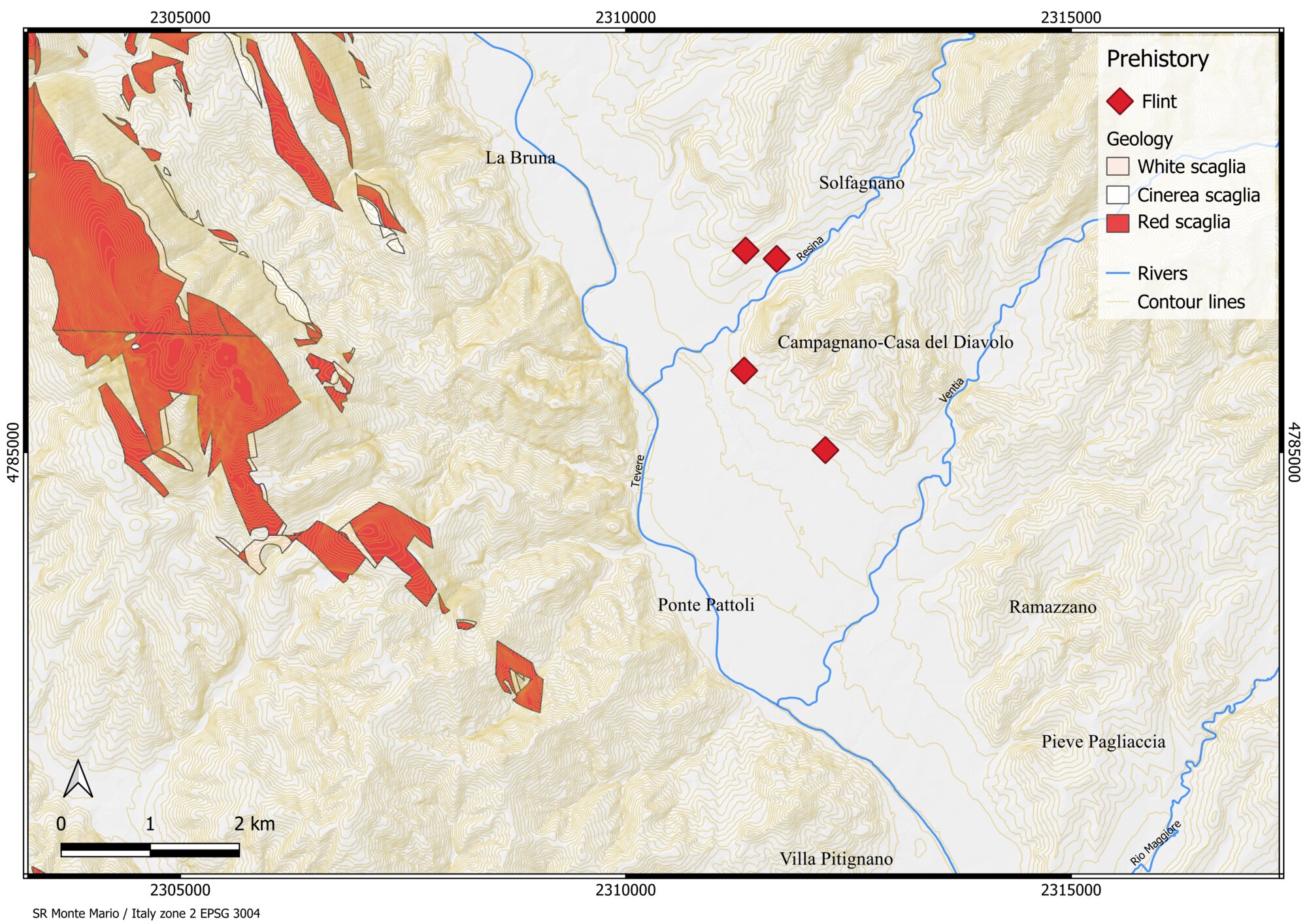

Regarding the territory examined here, all the collected Prehistoric material consists of lithic artifacts, e.g. flint. These are concentrated in the central-northern area, mainly near Casa del Diavolo and Resina (Figure. 5), not far from the secondary watercourses and tributaries. They are completely absent in the southern area of the examined territory. The lithic industry artifacts found here document the frequentation of the area; in fact, there are no surface concentrations suggesting the presence of substantial underlying deposits related to stable settlements. A general analysis of the distribution of artifacts has shown a preference for valley contexts along the terraced alluvial deposits and eluvial colluvial cover. In this context, Prehistoric occupation seems to be linked to the exploitation of flint, which is abundant due to the presence of pebbles as a result of the Ventia and Resina Rivers’ deposition. Moreover, the examined areas are in proximity to the outcrops of Red Scaglia (Cretaceous and Tertiary) in the Perugia Massifs, especially near Mounts Tezio and Acuto.

Along the Tiber riverbank, in the area investigated in this study, there is a significant absence of documentary evidence for the Proto-villanovian and Villanovian periods and for the subsequent ones. The valley does not seem to have been populated at all, whereas high areas at approximately 930 and 960 m a.s.l. were preferred, as evidenced by the hillforts on Monte Tezio (Matteini Chiari and Mattacchioni 2008) and Monte Acuto (Cenciaioli 1992), as well as by the evidence from the southwestern suburb of Perugia (Cenciaioli 1991, 97-104). Similar to other major centres in the region, such as Orvieto (Colonna 1985; Stopponi 2014) and Gubbio (Malone and Stoddart 1994; Negro et al. 2024), Perugia developed during the Villanovian period from a series of small settlements between Colle Landone and the Monte del Sole hills, with a phase of occupation dating from the late 10th to the 8th centuries BC (Feruglio 1990; Bartoloni 2002).

Hellenistic - Late Republic (3rd/2nd century BC - first half of 1st century BC)

Compared to the situation previously described, starting from the Archaic period there was an increase in the population within the territory of Perugia. Here and in the immediate southern and southeastern suburb, there is a much greater concentration of archaeological evidence. This is closely related to the formation of the city-state (Cenciaioli 1991, 97-104): from the early 6th century BC, people were attracted by the increasing role of Etruscan Perugia. This phenomenon is evidenced by the appreciable increase in settlements as highlighted by the necropolises of the 6th and 5th centuries BC and then in those of the 4th and early 3rd centuries BC (Di Stefano et al. 2012, 10-11).

As for the area under investigation, it was only from the mid-3rd century BC that the development of rural settlements was observed. This occurred during the period of major urban renewal works of the main pre-Roman cities in the central area of the region, such as Perugia and Assisi (Di Stefano et al. 2012, 24-25). The published data regarding the studied territory are supported by two types of evidence: one epigraphic and two funerary pieces of evidence: the chamber tomb containing travertine cinerary urns of the “Assisian type” in the Ramazzano village (Dareggi 1972, 25), a cinerary urn found in the Solfagnano area (Cenciaioli 2004, 395) 3 and the Etruscan inscription found near the locality of Civitella Benazzone. This inscription dates back to the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC and could support Sisani’s hypothesis about the presence of an Etruscan centre in this area (Sisani 2007, 53-54).

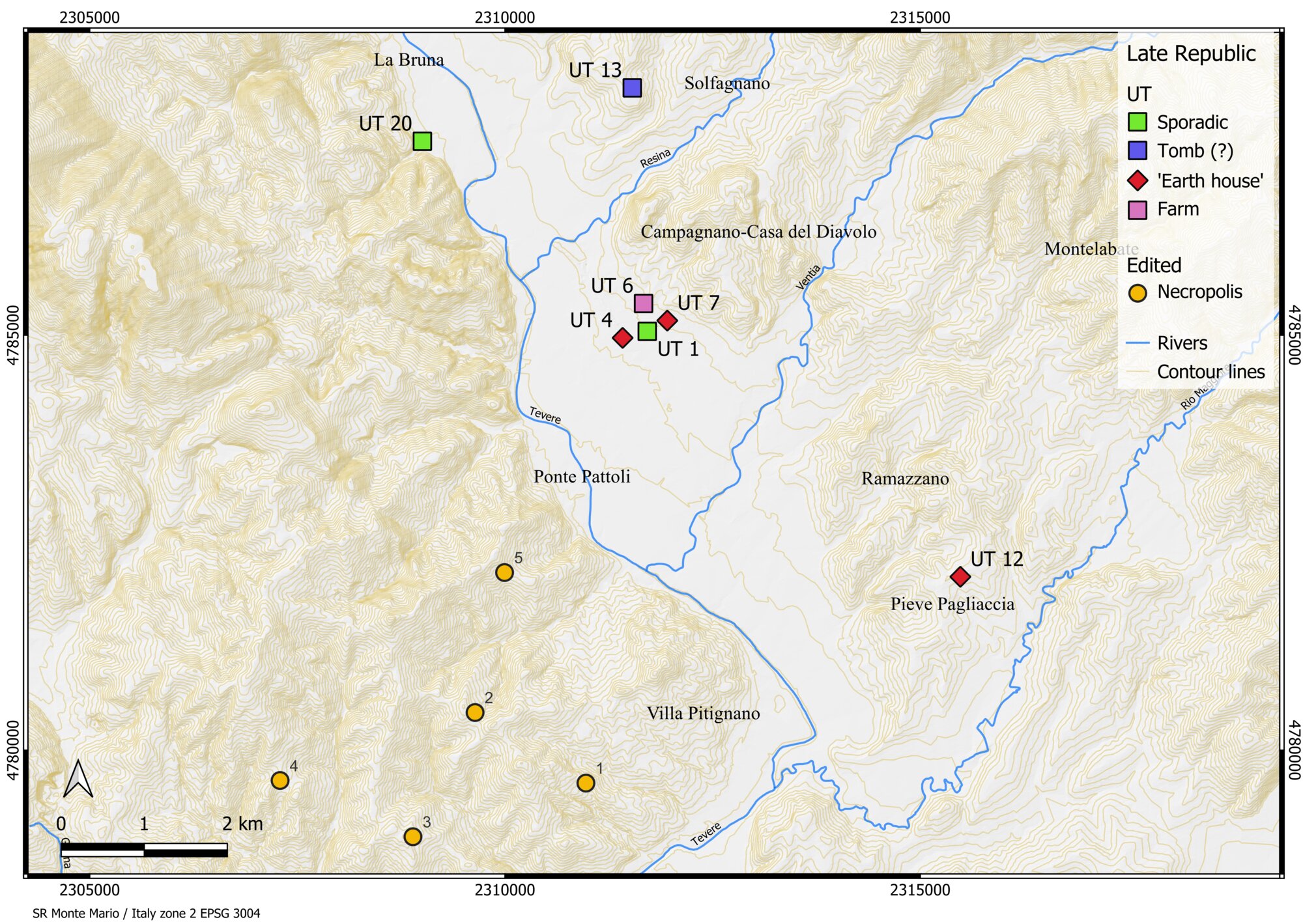

The data collected during the survey reveal only one context dating back to the 3rd century BC in the territory of Solfagnano (UT 13). The materials analysis showed that the site was abandoned around the early 1st century AD. The typology of materials found here, including a fragment of a bronze object (a ring?) and the handle of a large coarse pottery lid, suggests the presence of a funerary site. However, more data are still needed to confirm this hypothesis. This thesis could be supported by the discovery of a cinerary urn in the same area, now preserved at Villa Bennicelli in Solfagnano (Belardi et al. 2017). Also, in the area southwest of the studied territory, other funerary contexts are present (Cenciaioli 2004, 391): to the west of Villa Pitignano, the necropolises of Monte Giogo (Figure. 6, n 1) and Monte Bagnolo (Fig. 6, n 2); the necropolises in the Casamanza-Montelaguardia area (Fig. 6, n 3) San Marino (Fig. 6, n 4) and a tomb from the 3rd-2nd centuries BC in the Cordigliano area (Fig. 6, n 5).

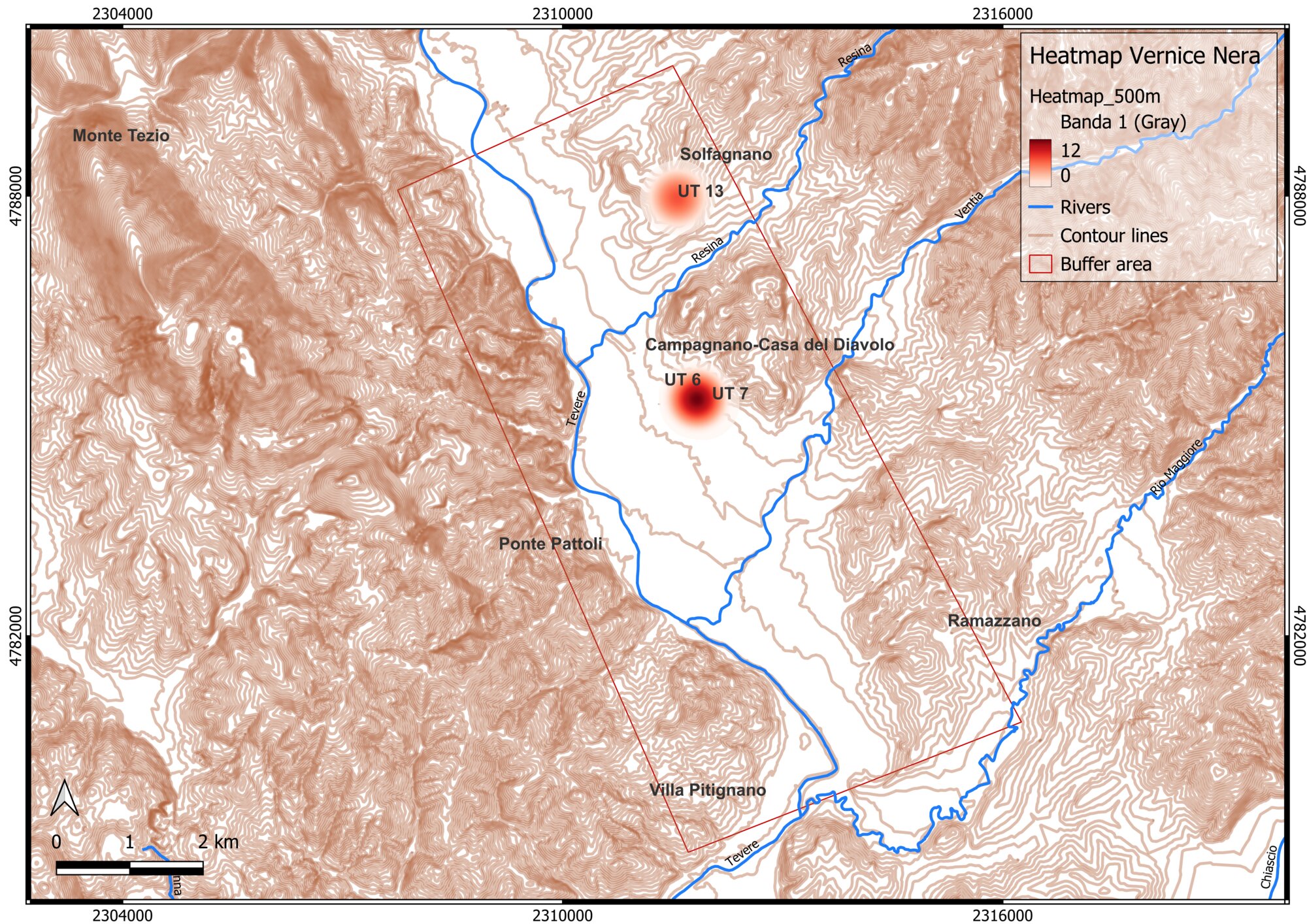

The other contexts identified through surveys date back to the 2nd century BC. Such contexts provide confirmation of the ‘Romanisation’ phenomenon, as documented by Roman finds, especially vernice nera (Figure. 7). The data seem to indicate a limited number of scattered settlements, mostly characterised by a few, though significant, pottery fragments, as evidenced by sporadic findings in the La Bruna area (Fig. 6, UT 20). At the southeast boundary of the studied territory, in the Colombella area, a concentration of evidence that may have belonged to a dwelling made of a presumably perishable material with brick covering was identified (“Earth house,” Fig. 6, UT 12). This is the only case in which dolia rims, morphologically similar to the Republican types have been found (similar in Braconi and Uroz Saez 1999, 168, fig. 13). In the central section of the studied territory, in the Campagnano-Casa del Diavolo area, a series of inhabited nuclei composed of structures made of perishable material and with brick covering (“Earth house” Fig. 6, UT 4) made of more durable materials such as rough and semi-worked stones, tiles, roof tiles, as well as paving blocks for opus spicatum flooring (Fig. 6, UTs 1, 6, 7) were found. The findings and materials were located within a radius of about 20 meters, thus indicating a close relationship between the described structures. UT 6 is quite interesting, as the analysis of the material distribution, especially vernice nera, coarse and fine potteries dating back to the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, suggests an “L” shaped concentration area of approximately 450 m². This context was interpreted as a farm.

Overall, the archaeological evidence identified for this period is scattered across an area of approximately 250 m², situated between 230 m (Tiber plain level) and 300 m a.s.l., generally favouring valley contexts corresponding to terraced alluvial deposits.

4.3 Early Mid Roman Empire (mid-1st century BC - early 3rd century AD)

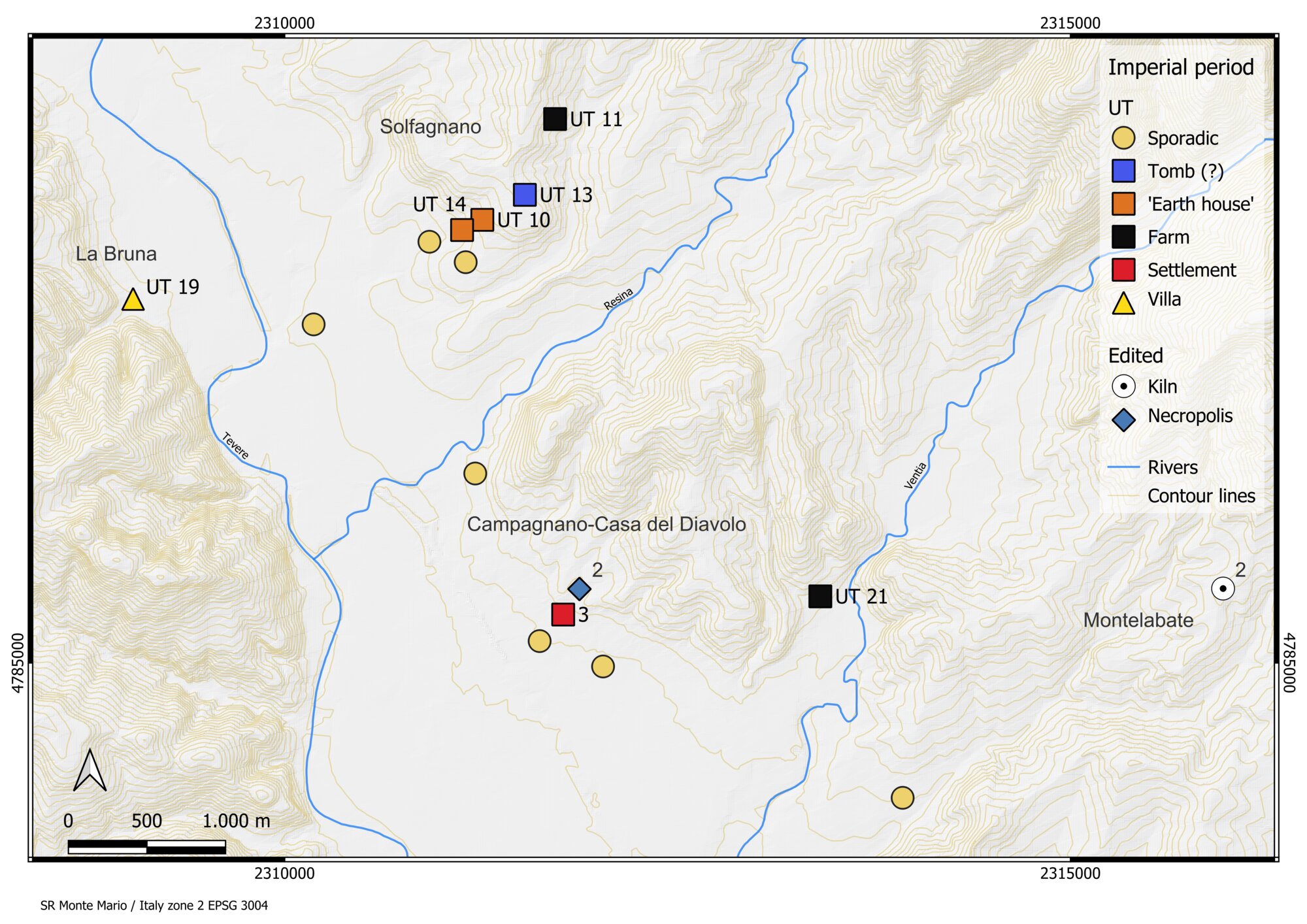

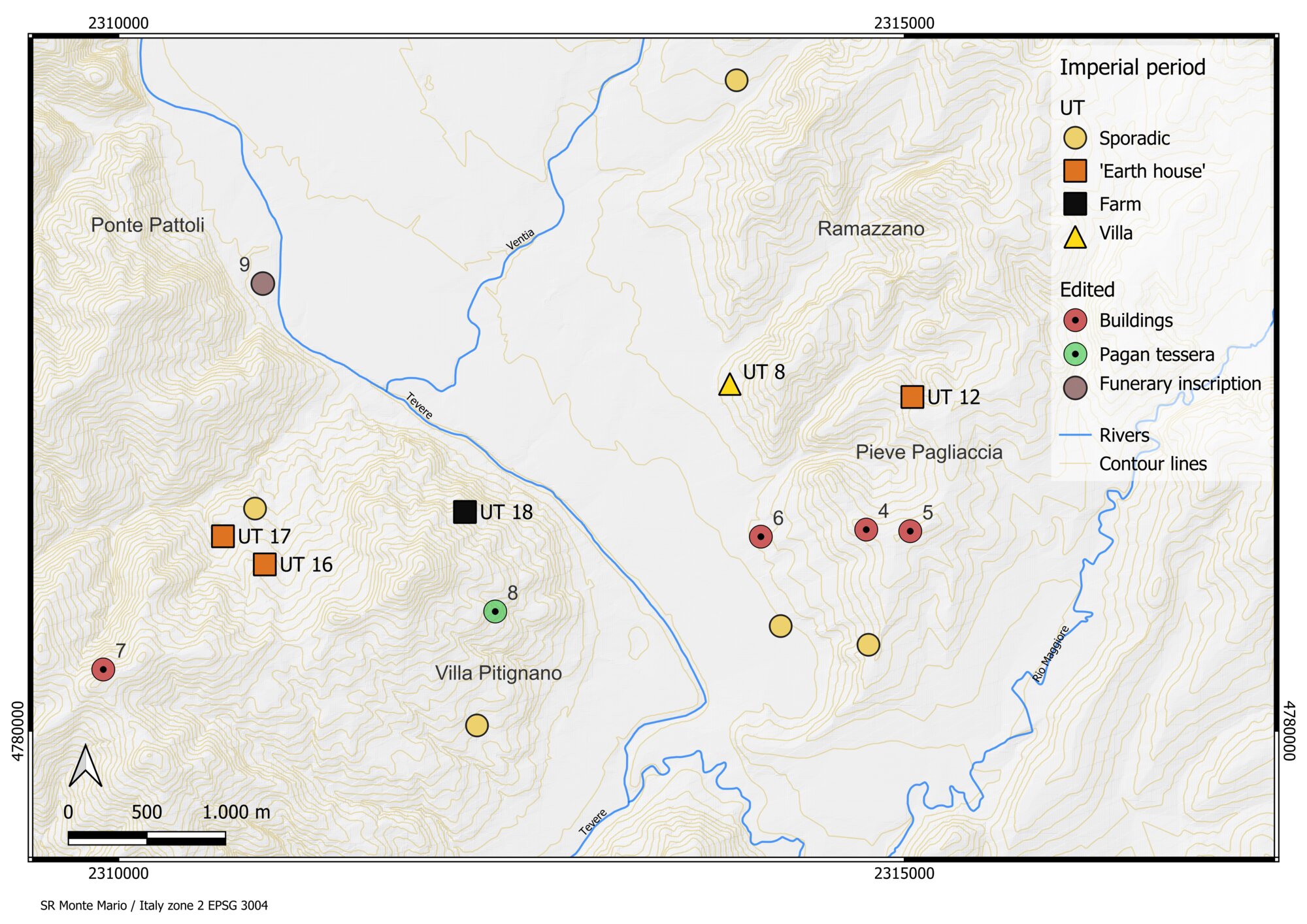

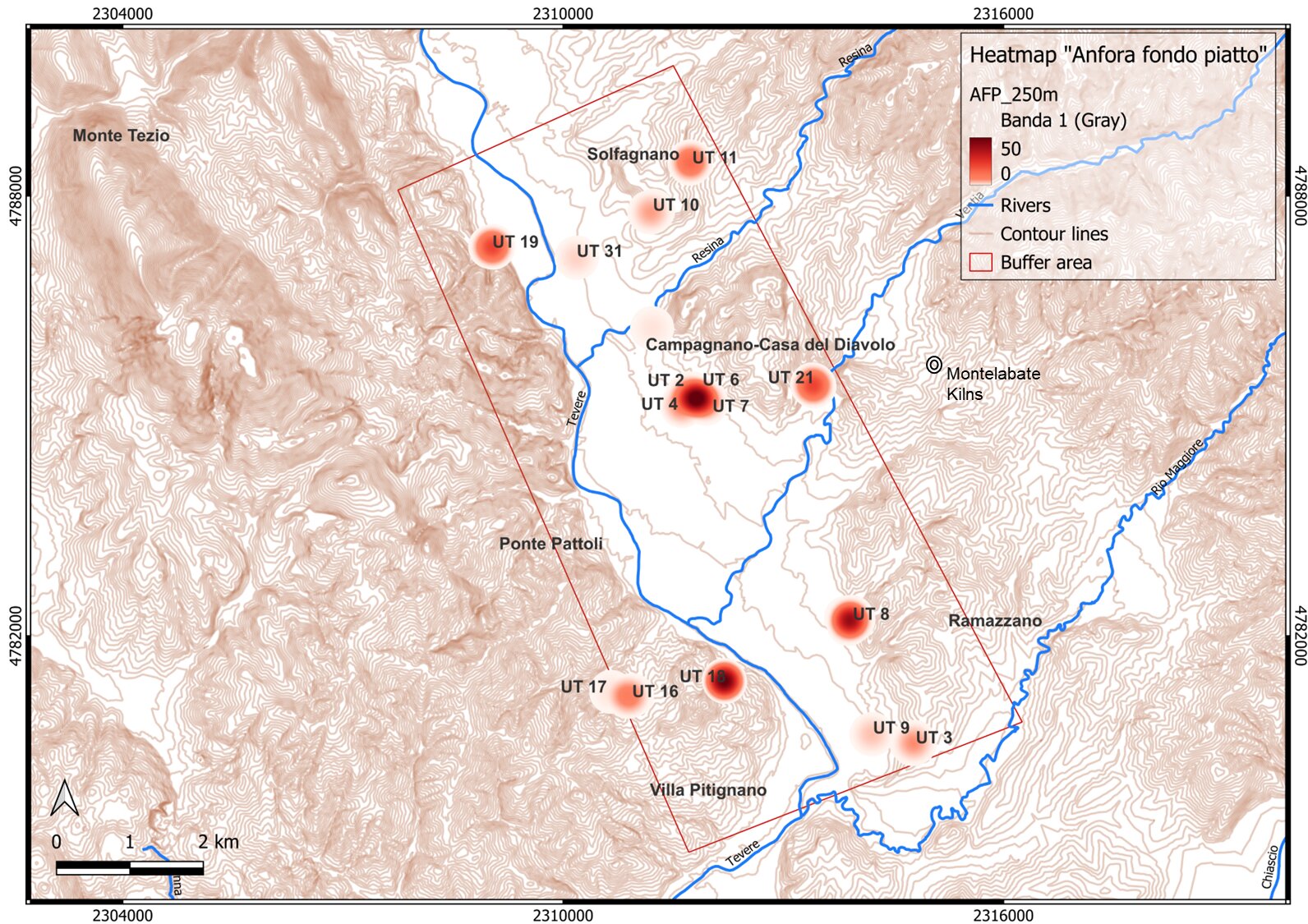

The number of settlements increased consistently from the Augustan period, thus characterising in a widespread manner the entire territory examined in this study, as can be seen in the rest of the surrounding Perugia landscape (Bratti 2007, 35-36). This increase may be a consequence of one of the most significant ancient conflicts that has marked the history of the city of Perugia and its territory, the Bellum Perusinum (41-40 BC): Octavian’s victory over Marcus Antonius’s brother, Lucius Antonius. This war was a step forward toward the final victory of the future Augustus over his rival and led to the expropriation of numerous lands in the countryside of Perugia, previously owned by local aristocracies, and to the destruction of a large part of the urban sector (Sisani 2006, 17; Cenciaioli and Sisani 2009, 179). The reorganisation of the territorial structure promoted by Octavian ensured new land assignments to his veterans and, from an archaeological perspective, this seems to correspond to the increase in settlements within the studied territory. Survey activities identified a total of twenty-six contexts (Figs 8-9). Economic and commercial activities related to the exploitation of natural resources and raw materials are also fundamental to the development of the territory. Timber and wheat from Umbria were among the two most demanded products in Rome (Diosono 2008, 252 ff.): Livy (Liv. XXVIII 45, 14-18) wrote that Perugia, with Chiusi and Roselle, supplied fir trees for shipbuilding and large quantities of wheat during the Second Punic War; Vitruvius also recommended fir and oak as the best woods for constructions (Vitr. II 9,5 and 8-9). Within such an economic and sociocultural context, the villa system prospered in this territory: archaeological field surveys have identified two rustic villae dating from the mid-1st century BC onwards. These production and residential sites are located on ancient geological deposits, such as river terraces, on eluvial-colluvial soils, at approximately 235 m a.s.l. near the Tiber River. The site selection for this settlement seems to be unusual compared to the general landscape of the central Umbrian territory, where this typology is attested at higher altitudes compared to smaller inhabited buildings (Di Stefano et al . 2012, 27). The first villa is located at the foot of the Pieve San Quirico (Fig. 8, UT 19) and is related to UT 20, dated back to the previous period. The deposit is heavily damaged due to the construction of a farmhouse that was built on the concentration area between 1954 and 1977, as shown in the historical satellite image. The second villa is in the Ramazzano area (Fig. 7, UT 8). The distribution of the material combined with aerial photography and three-dimensional modelling using UAV highlighted a complex internal structure consisting of various rooms and a series of oblique anomalies perpendicular to each other, perhaps related to a division of the land belonging to the villa (Mandorlo 2024, 6, fig. 6). This is the only context where it is possible to hypothesise an internal division between pars rustica and pars dominica . Thanks to the finding of square tubuli , the distribution of artifacts allows for the identification of the residential part of the villa, likely composed of rooms with opus spicatum and mosaic flooring, frescoed walls, architectural and marble decorations, and thermal structures located at the southwest corner of the concentration. The northward and north-eastward distribution of storage and transport amphorae could indicate the pars rustica of the villa. An interesting settlement evolution was observed in the late Republican context in the Campagnano Casa del Diavolo area (Fig. 6, UTs 1, 6, 7). In this phase, there was an intense reorganisation of inhabited spaces and a considerable expansion of their dimensions: it is no longer possible to separate the previously identified building units, as the material found is continuously distributed throughout the area (Fig. 8, n 3). There was a continuity of settlement life until the Late Antique period. From the analysis of the material distribution, the central role of this settlement is quite straightforward: a quantity of iron slag suggests the productive vocation of the context, and mosaic tesserae of different lithotypes, the floor and fragments of square tubuli , coloured intonaco fragments (red, yellow, green, black, and white), and a fragment of architectural terracotta suggest the presence of a modestly wealthy residential nucleus. The certain economic vitality of the area and its relationship with Rome, including the neighbouring and western Mediterranean areas, is also confirmed by the presence of amphorae containers, some produced locally, such as “fondopiatto” amphorae, and likely attributable to the Montelabate production site (Fig. 8, n 1) (Ceccarelli 2017; Ceccarelli 2021a), and other items produced in Spain. In addition to this central nucleus, other residential units were found in the settlement area, such as the context associated with the interpretative category of “Earth House”. The almost exclusive presence of large containers and amphorae, both locally produced and imported (Dressel 2/4 betica amphora), also suggest storage and warehouse spaces. Furthermore, the Imperial age necropolis, found at the end of the 20th century (Cenciaioli 2004, 395) and consisting of cappuccina tombs and a quadrangular funerary monument in opus caementicium covered with sandstone blocks (Fig. 8, n 2), suggests that this settlement played a key role in the territory, also considering its overall extension of ca. 7 ha. Within this settlement area, other rural buildings dating between the 1st century BC and the late 2nd/early 3rd centuries AD were found during the surveying activities in the northern area of the territory of the Solfagnano village (Figure. 8, UTs 10, 14) and in the southernmost area of the Villa Pitignano village. Two “Earth Houses” (Figure. 9, UTs 16, 17) and concentrations of materials related to heavily depleted underground deposits were located throughout the territory. In the Solfagnano area (Fig. 8, UT 11), Casa del Diavolo (Fig. 8, UT 21) and Villa Pitignano (Fig. 9, UT 18) areas, three farms were identified. The importance that these rural settlements had in Roman times is also indicated by their pivotal position: the first two farms are located along a presumed secondary road, whose routes possibly connected the valley with the territory of ancient Iguvium (Gubbio). The third farm is located in a significant area, in which it is possible to suppose that a secondary road connected it with the surrounding and inner territory of the Villa Pitignano village ( see below ). They are located at altitudes between 260 and 300 m a.s.l. These settlements are also associated with the already documented buildings ( Ville e insediamenti 1983, 84; Cenciaioli 2005, 217) located in the southeastern area of the territory: the Ramazzano-Colle delle Vigne (Fig. 9, n 4) and Colombella-Boschetto (Fig. 9, n 5) sites and a frequentation area at “La Volpe” (Fig. 9, n 6). Other documented findings, such as the sporadic site near Pieve San Sebastiano (Fig. 9, n 7) are not far from the settlement units identified in the Villa Pitignano area and located near the rich funerary contexts of Monte Giogo and Monte Bagnolo, as previously mentioned. Near the church in the historic village of Villa Pitignano (Fig. 9, n 8), a pagan bronze tessera which dates back to the 2nd century AD was found in 1872 and is now on exhibition at the National Archaeological Museum of Umbria (Rossi 1872, 16-17; Spadoni et al . 2018, 73 and 304-305). The small bronze object with dotted inscription has an eyelet for attachment ( CIL , XI 1947): as the inscription states it is a public document that the Magister pagi gave to the Pagus of Paetinianus during the lustratio religious ceremony, which was held annually for the sacred recognition of the boundaries of the pagus (Zaccaria 1994, 320-323). This finding indicates the presence of an important administrative site that gave the name to the current Villa Pitignano village. To complete this detailed picture of the territory, it is also important to mention a Latin funerary inscription found in the Ponte Pattoli area ( CIL , XI 1936) and dating to the Traianic period. This inscription relates to the presence of a hypothetical settlement, located near the current Ponte Pattoli village (Fig. 9, n 9).4.4 Late Antiquity (4th - early 6th century AD)

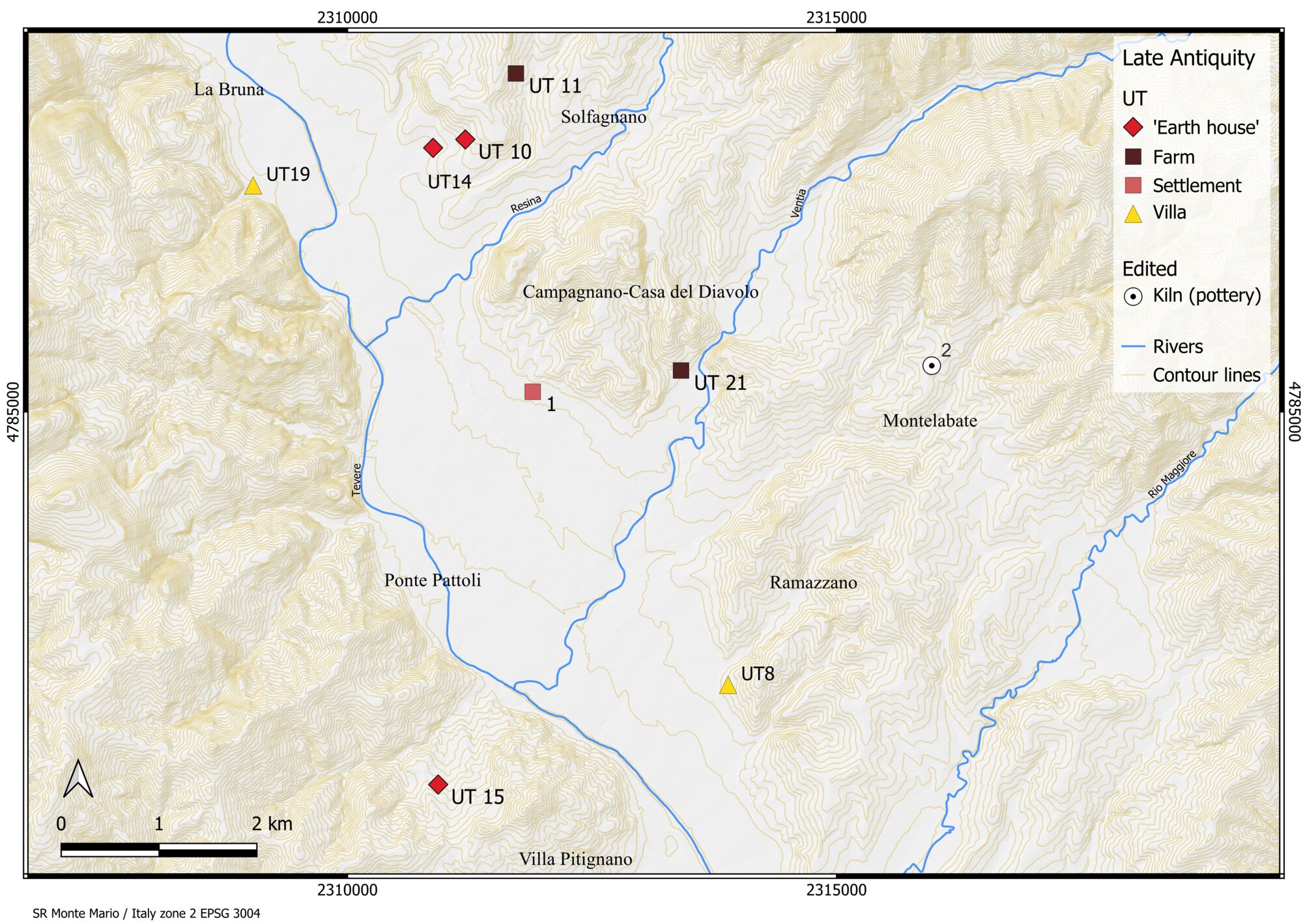

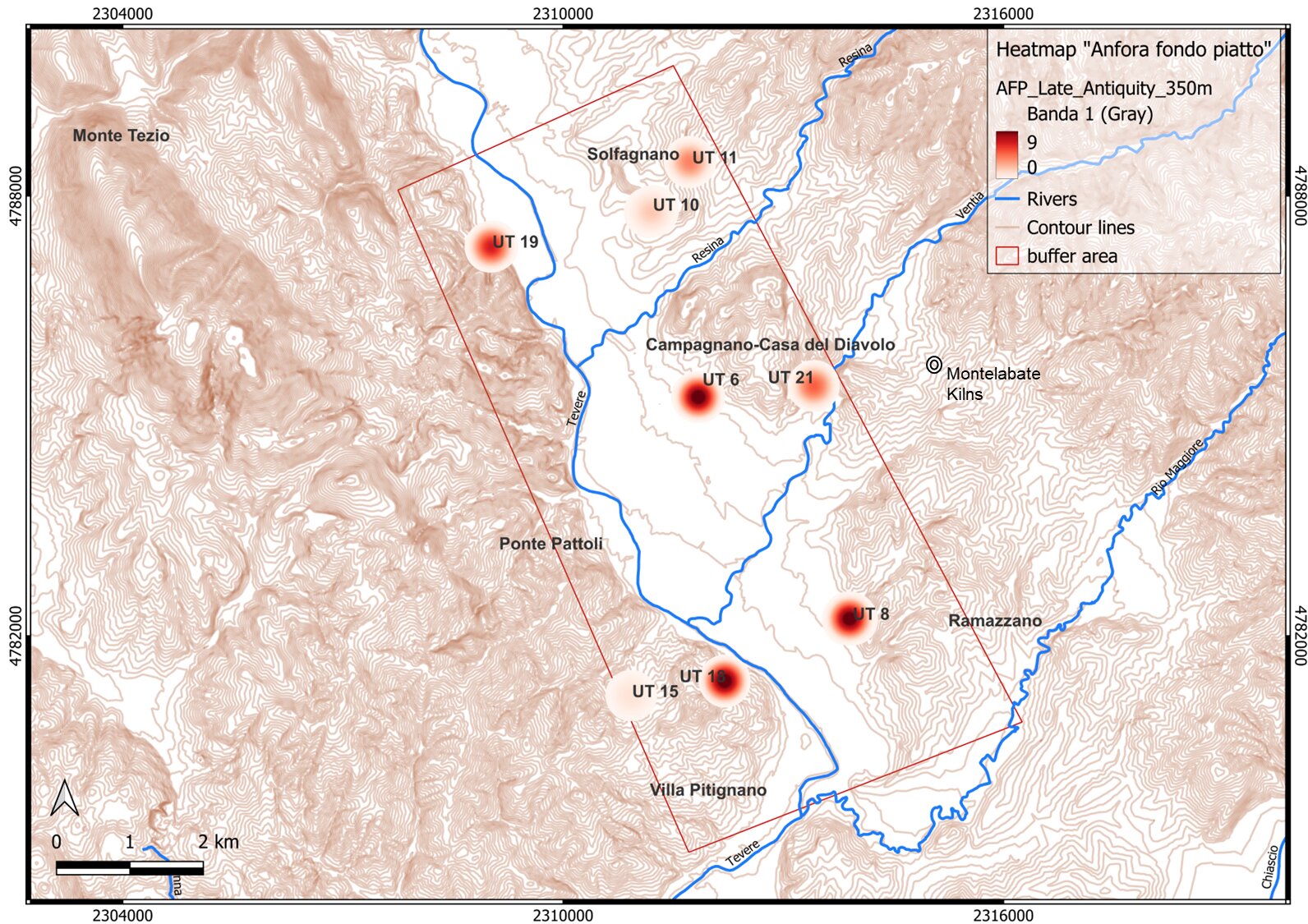

In the Late Antique period, starting from the early 4th century AD, the rural space seems to undergo a new economic change thanks to the interest of emperors Constantine, Valentinian, and Gratian, who promoted the restoration of main road axes and secondary roads (Di Miceli 2012). In the studied territory, this situation is evidenced by the reoccupation (or possible continuity of life) of some sites already existing and having arisen between the early 4th and early 6th centuries AD. This is documented by ceramic finds and coins of Constantine II (324-326 AD) and Constans Gallus (351-355 AD) ( see above Fig. 3c). The situation seemed to disappear during the Greco-Gothic war (535-553 AD). The settlement analysis shows that there is a reduction in the amount of evidence material compared to the Imperial period, from thirty sites to nine. This seems to have had little impact on the vitality of the social and economic structure of the territory. Some of the existing settlements have been reoccupied or simply continue to be inhabited, changing their size and shape. This phenomenon is documented in the Villa Pitignano area (Figure. 10, UT 15), which from the mid-4th century AD seems to undergo an expansion towards the east (Fig. 9, UT 16). This seems to have occurred also in the Solfagnano area (Fig. 9, UTs 10, 14). In the Campagnano settlement (Fig. 9, n 1), a decrease in the material found and a significant reduction in size are clearly attested in this phase. However, the settlement seems to maintain an important attractive role especially when compared to other sites of the territory. Towards the north and northeast, the presence of a fragment of Africana I and some other fragments of coarse ceramics found in the two Imperial farms (Fig. 9, UTs 11, 21) could suggest a form of seasonal reoccupation of the sites rather than continuous use from the Imperial period. The findings from the villa in the Ramazzano area (Fig. 9, UT 8) are different: these imported materials, such as a fragment of Tripolitana II amphora dating between the 2nd and 3rd centuries, a fragment of Africana I amphora and fragments of cooking pots showing morphological continuity from the 1st to the 5th century AD, and imitations of sigillata Africana could suggest a continuity of occupation of the site from the Imperial to Late Antique periods. In this period, the production of “ fondopiatto ” amphorae is well attested, as evidenced by findings and kilns from Montelabate (Fig. 9, n 2; Ceccarelli 2021b).4.5 Middle Ages (8th – 14th century AD) 4

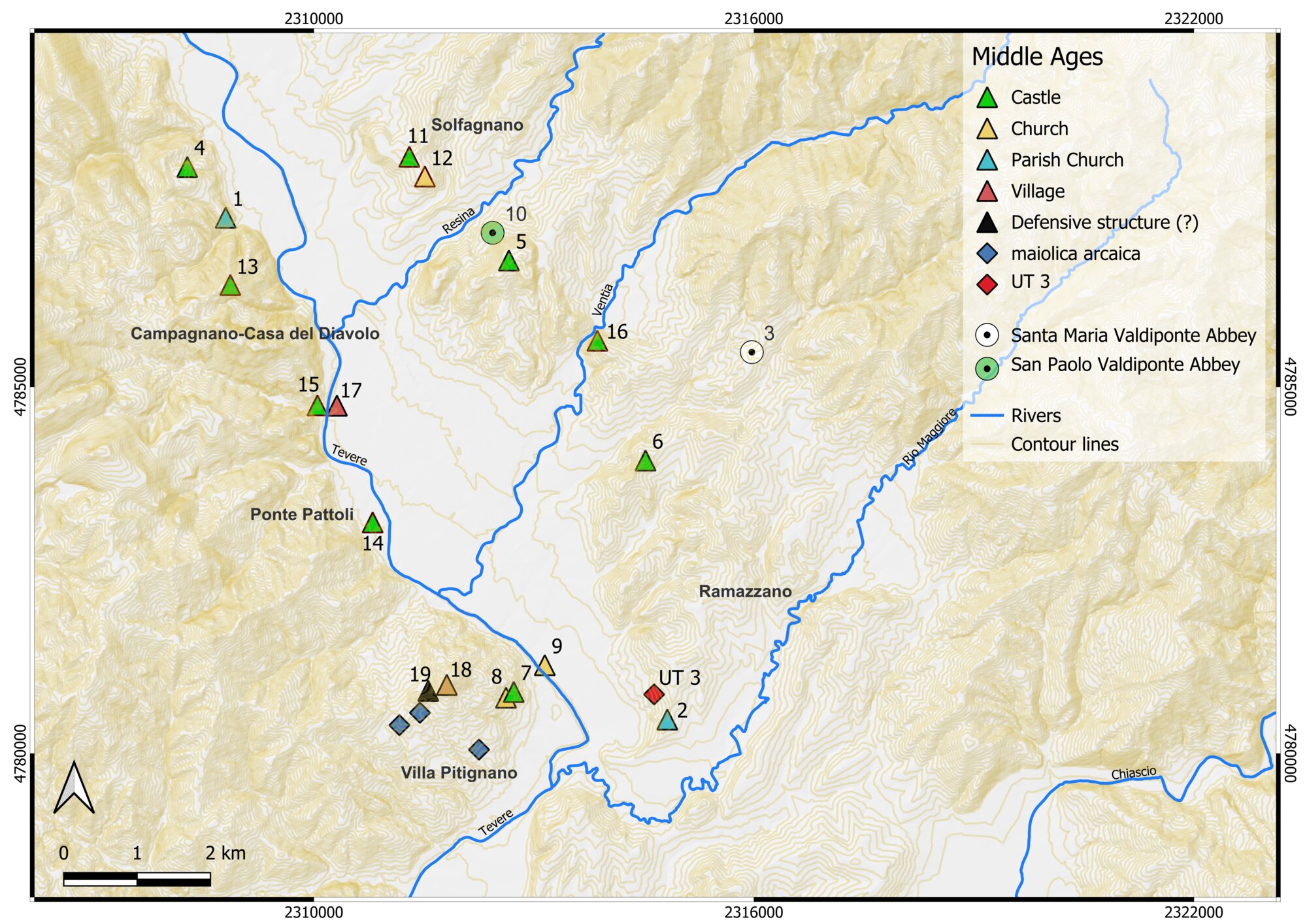

Information about the management of the territory and the transformations of the agricultural landscape that occurred between Late Antiquity and the early medieval periods in Umbria is rare, too rare for Perugia (Augenti 2018, 367-378). During the late 6th century AD, as seen in other areas of Byzantine Italy, the local administration of Umbria was reorganized. This is marked by the appearance of the exarch office and the creation of small internal Duchies (Zanini 1998, 59). At this time, the territory of Perugia – as well as that of Gubbio – was incorporated into the Byzantine corridor, where the Via Amerina plays a key role in connecting Rome with Ravenna (Scortecci 1991, 61-73). However, the territory described in this paper does not show any material evidence related to the Byzantine presence, whereas evidence of the Lombard passage is visible in the mention of “vila Francorum Ramancani” (Moretti et al . 1992, 167-186). “Ramaҫҫani” is a Lombard-origin anthroponym, and the toponym “Castrum Podij Gualdi” is mentioned as “Castle of Poggio Gualdo vestiges” in the map of the Catasto Chiesa (A.S.P., UTE, Catasto Chiesa, 1727, sheet 178). However, the survey activities near the lands associated with these toponyms has not yielded any evidence. The first territorial attestations in documentation concern the monastery of S. Maria Valdiponte. A document signed by Pope Giovanni XIII in November 969 regarding extensive and consolidated territorial possessions testified the existence of the monastery long before the mid-10th century (Fig. 11, n 3) (Ceccarelli 2021b, 332). Based on the edited historical documentation, the territory seems to have been populated from the 10th century and more fully from the early 11th century, matching with the phenomenon of the “ primo incastellamento ” (Francovich and Ginatempo 2000; Bianchi 2015, 163), a phase between the late 9th and 11th centuries. In this period, nine instances of monumental evidence are attested in the territory, including three castra : these are located at altitudes between 340 and 410m a.s.l. and are identified in the localities of Pieve S. Quirico (Fig. 11, n 4), Civitella Benazzone (Fig. 11, n 5), and Ramazzano (Fig. 11, n 6). The management of the castrum of Civitella, an attractive centre and important conjunction in the valley. It is first mentioned at the donation of two small plots of land for the salvation of the soul, given to the monastery of S. Maria Valdiponte in the mid-11th century AD, through which the monastery gained control over the castle and its possessions (DeDonato 1988, 44-46). The castle of Ramazzano was founded built and continuously inhabited by the Ramazzani family (“ Ramancani ”) until the mid-17th century. It is first mentioned in 1097, at the cessation of rights over some properties given to the monastery of S. Maria Valdiponte (De Donato 1988, 60-62). Originally, the complex structure of the castle was supposed to consist of four rectangular corner towers of which only the one located to the southwest remains intact. Although in a state of neglect, the Guelph-style battlements characterising the entire perimeter wall can still be seen. Further south, in the territory of Villa Pitignano, archaeological data prior to the archival documentation are not available. The first mention of the castle with a polygonal tower (Fig. 11, n 7) appears in relation to the construction of the church of S. Maria Assunta in a document dating back to at least the early 11th century and refers to the church located within the walls (Figure. 11, n 8) (Ricci 1936, 593; Angelucci 2011). A second church situated in the territory between Villa Pitignano and Ramazzano, the Church of S. Clemente (Fig. 11, n 9) mentioned in the archival documentation as “ ecclesiam S. Clementis in ripafluminis ” was built on the alluvial plain near the Tiber River – now Villa Simonetti. This religious building, the only one in a flat context, must have been a point of great political relevance and control over the crossing of the Tiber River. Many of the possessions in the territory and the mentioned churches were divided between the properties of the Benedictine abbeys of S. Maria di Valdiponte di Montelabate and S. Paolo di Valdiponte (Fig. 11, n 10). The latter was most likely founded by S. Maria Valdiponte’s monastery and it “ always remained the mother abbey in relation to it ” (Ricci 1935, 38). Excavation surveys carried out between 1971-73 document the life of the abbey between the 10th and 17th centuries (Adams et al . 1972; Blagg 1975, 360). Two parish churches are documented in the territory; their origin can be traced back to this period, even though, at the current state of research, they are not mentioned in documents prior to the early 11th century (Maiarelli, 2006, 44; Ricci 1936, 7-10). To the north is Pieve S. Quirico (Fig. 11, n 1), known as Plebis Sancti Quirici , and to the southeast, Pieve Pagliaccia (Fig. 11, n 2), known as Plebem de Palacio (“Pieve del Palazzo”). The current documentary incompleteness can be partially overcome by the materials found during survey activities. A few hundred meters from the first parish church, surveys permitted identification of the already mentioned villa in the Bagnara-La Bruna area, which shows human presence until the 5th century AD. Near the second parish church, surveys have revealed a context related to the Imperial period, and occupation of the area remained continuous until the central centuries of the Middle Ages (Fig. 11, UT 3). On the one hand, these elements can suggest the possibility that the parish church overlaps those of the Roman/Late Antique periods (Campana et al . 2008); on the other hand, it is possible that in the Late Antique period the territory could already have been divided into parish districts, as highlighted in another peninsula territory (Fiocchi Nicolai and Gelichi 2001, 304-307) and organised in the cura animarum (Violante 1982, 972-992). Between the late 11th and early 12th centuries, there was a new economic and demographic growth, which was motivated by the increasingly important role played by the Comune of Perugia (Grohmann 1981). The structuring of the territory is also characterised by the presence of small fortified inhabited centres, now lordly residences, and new religious buildings. All of them built in the summit areas, at altitudes between 300 and 480m a.s.l., strategically dominating the Tiber Valley. Some fortified sites identified in the territory are documented in textual sources from the mid-12th century: the castle of Solfagnano (Fig. 11, n 11) with the Church of S. Silvestro (Fig. 11, n 12), the castrum of S. Giuliano (Fig. 11, n 13) located at the foot of Monte Tezio at an altitude of 485m a.s.l., the present village of Ponte Pattoli (Fig. 11, n 14), the castrum Rustichelli in the Prozonchio-P. Pattoli area (Fig. 11, n 15) and the Carestello to the east (Fig. 11, n 16). From the second half of the 12th century, the existing fortified settlements are transformed into large settlements, and new villages are formed even in lowlands. The formation of new villages is documented in the Ponte Pattoli area starting with the foundation of La Fratticiola village (Fig. 11, n 17) located near the Tiber River. In this period, in the area of the Villa Pitignano village, survey activities evidenced a human occupation as demonstrated by the sporadic nature of fragments of maiolica pottery (Fig. 11, blue point). In the same area, on the top of the hill and below the Santa Croce church, mentioned for the first time in the mid-13th century (Fig. 11, n 18; Ricci 1936, 593), survey and analysis of aerial and historical images from IGM of 1954-55 have allowed identification of the presence of a structure. During the field-walking survey a perimeter wall built in sandstone, which measures ca 7 x 20 m, was found. The presence of some slits, several postholes and a perimeter wall could suggest some sort of defensive structure (Fig. 11, n 19), even if this is not mentioned in archival documentary sources. However, in the late 19th century, the finding of a plaque may still suggest the possibility that the remaining structure could be attributed to the castrum, or oppidum already mentioned in the epigraphic evidence (Rossi 1872, 118). The identification of large accumulations of rubble stones and bricks to the north and northwest of the site could suggest the presence of an inhabited area in the medieval period. This site may be the second settlement mentioned in archival documentation around the mid-13th century in the historical documentation of “Villa Pitignani” (Ricci 1936, 593) 5 .Conclusion

The topographic survey described in this paper has highlighted the high archaeological value of the studied territory (a total of 32 Topographic Units). The data offer a significant contribution to the understanding of ancient settlement dynamics. Prior to this survey carried out on the portion of territory located northeast of the city of Perugia, most attestations were related to the medieval period, such as settlements, churches, and abbeys. However, few records referred to the Etruscan and Roman periods and those related to the Pre-Protohistoric period were completely absent. Thanks to the interpretation of the archaeological data collected, not least from the late Republican period, it is now possible to observe an articulated and densely populated area. The archaeological data concerning the phase prior to the Roman and medieval periods are still very scarce. This lack of data can be attributed to the different survey methods used for the identification of Prehistoric and/or early medieval contexts combined with the experience and attention permitting recognition of material from that period. This is the main cause of the general “non-visibility” (Pizziolo et al . 2009, 222; Campana 2009). Furthermore, the visibility factor decreases significantly in certain areas, such as alluvial plains, due to the continuous deposition of material and to landslides, post-depositional phenomena and the presence of dense vegetation leading to the obliteration of any underlying deposits (Belvedere 2010). Surveys have shown concentrations of lithic artifacts from the Prehistoric period exclusively in the central-northern area. Analysis of the distribution of these finds has highlighted a preference for the valley due to the presence of terraced alluvial and eluvial-colluvial deposits, near secondary watercourses. The studied territory presents a documentary void for this period which, seems to continue at least until the Archaic period. The first significant attestations in the examined territory can be identified between the second half of the 3rd and the beginning of the 2nd century BC. This is evident in the surrounding territory, e.g. Civitella d’Arna (Donnini and Rosi Bonci 2008), Montelabate (Stoddart et al . 2012), along the middle Tiber Valley ( Tiber Valley Project in Di Giuseppe 2005) and more generally in central Etruria (Potter 1979; Patterson et al . 2020, South Etruria Survey Project ), where small-sized residential units are found distributed sparsely throughout the territory. The spatial distribution of the survey evidence suggests a certain preference for flat areas, near terraced alluvial deposits along secondary watercourses and not far from the Tiber River. Furthermore, a subsistence economy can be inferred from the analysis of the ceramic material. This is linked to agricultural exploitation and some limited contact with the external market evidenced by the faint presence of vernice nera pottery. The survey data do not permit an interpretation related to funerary contexts during this and the following periods, but only to buildings, sporadic and frequented contexts. The possible exception could be the context in the Solfagnano area. Between the mid-1st century BC and the 1st century AD, there was a great increase in settlements in the territory, which with few exceptions continued without interruption until the period between the end of the 2nd and the beginning of the 3rd century AD. In the territory of Perugia, this increase was linked to the completed ‘Romanisation’ of the city of Perugia from 130 BC with the election of the new consul Paperna and to the acquisition of Roman citizenship in 89 BC (Sisani 2007, 62-64). This outcome was further enhanced by the territorial reorganisation and the viritane allocations to which the territory was subjected during the Augustan and Tiberian periods (Sisani 2009, 54). It was precisely in this phase that there was a significant development of medium-sized rural settlements and villas, generally for self-consumption and possibly for short-range trade (Vaccaro et al . 2009, 289). A short-range trade is suggested involving several fragments of “ fondopiatto ” amphorae from Montelabate kilns (Ceccarelli 2021a). These fragments were identified on 2/3 UTs attributed to the Imperial period, and for this reason we can consider the “fondopiatto” amphorae as a guide fossil of the examined territory (Figure. 12). Moreover, this element suggests that the main product of the territory is wine. At the same time, imported material found in many UTs could suggest interesting contacts between this central area and other parts of the Umbria region or other regions of the peninsula. Some fragments of terra sigillata most likely produced in the Tuscan region or in the southern territory of the Umbria region – several forms of terra sigillata are similar to those produced at the Scoppieto kilns, Terni (Bergamini 2008) – and a few fragments of pareti sottili – some of which are similar to the those of the kilns in the locality of Vittorina, Gubbio (Cipollone 1988) – suggest contacts as well as medium and log-range trade. In all these cases it is clear that the Tiber River as well as the roads played a key role in the commerce. Finally, the identification of imported amphorae from Baetic and North African contexts supports hypotheses about certain types of trade even on a Mediterranean scale. Based on the types of amphorae found, it can be inferred that oil and fish sauce were mainly imported, at least during the Imperial period. Therefore, between the 1st century BC and the 3rd century AD, the territory appears to have been richly articulated with numerous settlements as evidenced in the Civitella d’Arna area (Donnini and Rosi Bonci 2008) and around Perugia ( Ville e insediamenti 1983 ). This settlement network emphasizes the focal role of villae and the Campagnano settlement. The calculated distance in a GIS environment between the Ramazzano and Bagnara-La Bruna villae and the settlement is exactly 3.7 km (= 2.5 Roman miles). The distribution analysis of the rural settlements suggests the presence of a precise settlement model based on a system of perches of five centuries, the so-called pertica quintaria composed of an irregular square of 20x17 actus (Camerieri and Mattioli 2013; Camerieri and Mattioli 2014, 122). The settlement model became more complex when inserted into a specific administrative framework, where the territorial entity of the pagus was the smallest possible unit enjoying partial administrative freedom of the municipium of Perusia . The pagan tessera found near the Villa Pitignano castle and the set of contexts identified around this locality support the hypothesis of the presence of the administrative center. Between the pagus area and the villa of La Bruna area the distance calculated on the reclassify DEM in a GIS environment corresponds to ca 8.5 km (= 6 Roman miles) (Mandorlo – in press ). This allows us to suppose that this portion of the territory was probably divided by two main roads on either side of the Tiber River. However, we do not know much about the roads that could have connected all these buildings. The main hypothesis is that one of the ancient routes corresponds to the Tiberina Nord road (Cenciaioli 2015). Even though the study is still in progress, the calculation in QGIS and photo interpretation of the satellite and historical orthophoto anomalies suggest an alternative orientation and development path. Between the 3rd and 6th century AD, the analysed territory shows a decrease in settlement units compared to the Imperial period, and for some of them, it is only possible to hypothesize a certain life’s continuity. The studied territory seems to develop a countertrend compared to regional dynamics, where a general break is already evident from the 5th century AD onwards (Di Stefano et al . 2012). The main contexts examined in the territory seem to survive until the beginning of the 6th century AD, as evidenced by the production of pottery and “fondopiatto” amphorae from the Montelabate kilns (Ceccarelli 2021b, 329-330), which met the territory’s demands. Moreover, the fragments of “fondopiatto” amphorae represent again the guide fossil for the attestation the UTs at the Late Antique period (Figure. 13). The socio-economic and political crisis generated by the Greco-Gothic war (535-553 AD) seems to be a significant moment of rupture contrary to many regional realities (Di Giuseppantonio et al . 2003, 1378). By the end of the 6th century AD, Perugia and its territory along the Tiber Valley were part of the ‘Byzantine corridor’ (Menestò 1999, 117-127). The reorganisation of the agricultural landscape, between the 7th and 8th centuries AD, which was recorded in other areas of the peninsula, such as Tuscany (Farinelli 2007, 47-48), does not seem to find a counterpart in Umbria. The archaeological data for these centuries are significantly inconsistent probably due to the lack of targeted research to understand the early medieval agrarian landscape (Augenti 2018, 367-378) in addition to the archaeological invisibility of the surface. Although we currently do not have any material evidence that can help us understand the evolution of settlements during the early medieval period, it is difficult to hypothesize a total absence of human activity in the territory, as evidenced in other areas of central Italy (Campana et al . 2008). From a reading of the survey data and its comparison with the monumental emergences of the territory, an interesting fact emerges: the main fortified nuclei and the two parish churches were built near the villae , the settlement, and the pagus . Although it is not yet possible to establish a connection between Roman and Late Antique contexts with castra and parish churches, the data cannot be completely overlooked (Violante 1982). Only 250 m from the Roman-Late Antique villa in the La Bruna locality, the Church of S. Quirico was constructed; 1.5 km from the Campagnano-Casa del Diavolo settlement the castrum of Civitella Benazzone was established; 1.8 km from the Ramazzano villa the homonymous castrum was built; probably at the location of the pagus Paetiniano , the castrum with the church of S. Maria may have been built and in the Pieve Pagliaccia area with small residential units a parish church may have been built. During the following centuries, the rural landscape was articulated in a complete manner with fortified villages and churches ( Catasto Giudiziario del Podestà, A.S.P., 380r-415r, 1258). The archival documentation reveals that the “ primo incastellamento ” in Umbria was to begin from the 11th century. The absence of targeted excavation surveys leaves open the question of the origin of the first settlements (Augenti 2018, 371-372). Archival sources furthermore reveal, that certainly from before the 10th century, a territory was divided among the major ecclesiastical entities through land donations made to the Church of S. Pietro and the Cathedral of S. Lorenzo in Perugia and to the Benedictine abbeys of the territory (Grohmann 1981). From the last decades of the 11th and the beginning of the 12th century, there was a widespread distribution of fortified sites, which were equipped with walls or other defensive elements, such as ditches and embankments. The lordly residences were the most direct evidence of a new political and economic stability of the Municipality of Perugia, which was fully extended into the territory. In conclusion, the study carried out on the territory northeast of the city of Perugia along the Tiber Valley has highlighted a richly articulated palimpsest, a result of transformations that have occurred over time. These transformations are still visible in the contemporary landscape and others are preserved in the memory of the people who have been part of it.Acknowledgements

First, my sincere thanks go to Professor Stefano Campana (University of Siena) for his support and teaching during my master’s degree. His encouragement and trust in me were fundamental during the whole project process. Thanks again for providing me with the instrumentation of LAPeT Lab (Lab of Landscape Archaeology and Remote Sensing) and his experienced know-how.

Thanks also to Dr. Giorgio Postrioti, inspector of Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio dell’Umbria for his availability and support.

I am very grateful to Federica Benda Cucinelli for her financial support, which was necessary for organizing the entire survey and activities with the team. I take this opportunity to thank several people, colleagues and students from different Italian universities, many of whom are also my great friends. Here are some of them: Maria Teresa Sgromo, Vincenzo Golia, Chiara Mendolia, Debora Tanganelli, Noemi Pochini, Stefano Brizioli, Manlio Guardabassi, Tatiana Semiletki, Benito Goglia and Francesca Raiti. Other colleagues and students supported me during the laboratoriy phases: Francesco Paratico, Benedetta Baleani, Elisabetta Ponta, Eleonora Andreini and Giuseppe Prospero Cirigliano. All of them have given me important advice and support.

My thanks also go to Dr. Letizia Ceccarelli for the scientific exchange that developed during the laboratory activities, especially for studying the pottery collected during the field-walking survey.

Thank you to Francesco Raggetti and other local people I met during the study. Their passion and dedication were much appreciated.

References

- Adams, I., A. T. Luttrell and Toker, F. K.B. 1972. An Umbrian Abbey: San Paolo di Valdiponte, I, Papers of the British School at Rome, 40: 145-195.

- Angelucci, P. 2011. Le carte che parlano: l’Archivio Storico dell’Abbazia di San Pietro in Perugia. Perugia: Ali&No.

- Augenti, A. 2018. L’incastellamento in Umbria: una prospettiva archeologica. In L’incastellamento: storia e archeologia. A 40 anni da Lesstructures di Pierre Toubert, edited by A. Augenti and P. Galetti: 367-78. Spoleto: Fondazione Centro italiano di studi sull’alto Medioevo.

- Attema, P., Bintliff J., Van LeusenM., Bes P., de Haas T., Donev D., Jongman W., Kaptijn E., Mayoral V., Menchelli S., Pasquinucci M., Rosen S., García Sánchez J., Gutierrez Soler L., Stone D., Tol G., Vermeulen F. and Vionis A.2020. A guide to good practice in Mediterrean surface survey projects, Journal of Greek Archaeology, 5, 1-62.

- Bartoloni, G. 2002. La cultura villanoviana all’inizio della storia etrusca (edizione aggiornata), Roma, Carocci editore.

- Belardi, P., Merli S., and Pineiro, M. 2017. Il castello di Solfagnano. La natura del bel paesaggio, Perugia: ABA PRESS.

- Bellucci, G. 1915. L’epoca paleolitica nell’Umbria. In Archivio per l’Antropologia e l’Etnologia 44, 289-324. Firenze: tipografia di M. Ricci.

- Belvedere, O. 2010. La ricognizione di superficie. Bilancio e prospettive. Journal of Ancient Topography XX: 31-40.

- Bergamini, M. 2008. Scoppieto e i commerci sul Tevere. In MarcatorPlacidissimus. The Tiber Valley in Antiquity. New research in the upper and middle river valley, edited by F. Coarelli and H. Patterson (Atti del Convegno, Roma, British School at Rome, 27-28 febbraio 2004): 279-315. Roma: Edizioni Quasar.

- Bianchi, G. 2015. Recenti ricerche nelle Colline metallifere ed alcune riflessioni sul modello toscano. Archeologia Medievale: cultura materiale, insediamenti, territorio XLII, 2015: 9-36.Firenze: All’Insegna del Giglio.

- Blagg, T. F.C. 1975. Civitella Benazzone (Perugia): scavo dell’abbadia medievale di San Paolo di Valdiponte (Abbadia Celestina). In Archeologia Medievale, 2: 359-66. Firenze: All’Insegna del Giglio.

- Braconi, P., and Uroz Saez,J. 1999. La villa di Plinio il Giovane a S. Giustino. Primi risultati di una ricerca in corso. Ponte S. Giovanni: Quattroemme.

- Bratti, I. 2007. Forma urbisPerusiae, Città di Castello: Edimond.

- Cambi, F., and Terrenato,N. 1994. Introduzione all’archeologia dei paesaggi. Roma: La nuova Italia scientifica.

- Camerieri, P., and T. Mattioli. 2013. Un filo rosso di duemila anni fa? Le alluvioni del Tevere e del Nera in un provvedimento del Senato Romano. In L’Italia dei disastri, edited by E. Guidoboni and G. Valensise: 19-26.Bologna: Bononia University Press.

- Camerieri, P., and T. Mattioli. 2014. Il paesaggio centuriato di TifernumTiberinum e Perusia: prime considerazioni. In La Media e Alta Valle del Tevere dall’antichità al medioevo(atti della Giornata di Studio, Umbertide, 26 maggio 2012), edited by D. Scortecci: 29-62. Città di Castello: Daidalos.

- Campana, S. 2001. Carta archeologica della provincia di Siena. V. Murlo, Siena: Nuova Immagine Editrice.

- Campana, S. 2009. Archaeological Site Detection and Mapping: some Thoughts on Different Scale of Detail and Archaeological “Non-visibility. In Seeing the unseen. Geophysics and landscape archaeology, edited by S. Campana and S. Piro: 5-27. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Campana, S. 2015. Archeologia dei paesaggi medievali della Toscana: problemi, strategia, prospettive.In Medioevo, paesaggi e metodi, edited by F. Saggioro and N. Mancassola: 25-50. Mantova: SAP.

- Campana, S. 2018. Mapping the Continuum: Filling ‘Empty’ Meditteranean Landscapes. New York: Springer.

- Campana, S., C. Felici, R. Francovich, and F. Gabbrielli. 2008. Chiese E Insediamenti Nei Secoli Di Formazione Dei Paesaggi Medievali Della Toscana. Atti Del Seminario (San Giovanni D’Asso-Montisi, 10-11 novembre 2006). Firenze: All’Insegna del Giglio.

- Campana, S., and Forte, M. (Eds). 2017. Digital Methods and Remote Sensing in Archaeology. Archaeology in the Age of Sensing. New York: Springer.

- Ceccarelli, L. 2017. Production, and trade in central Italy in the Roman period: the amphora workshop of Montelabate in Umbria, Papers of the British School at Rome, 85: 109-141.

- Ceccarelli, L. 2021a. Nuovi dati di scavo sulla produzione di anfore in Umbria tra Tevere e Chiascio nel I e II secolo d.C., FOLD&R Italy Series, 508: 1-19.

- Ceccarelli, L. 2021b. Ceramic production in the Late Antique and Early Medieval territory of Perugia. Archeologia medievale: cultura materiale, insediamenti, territorio, XLVIII. 323-334. Firenze: All’Insegna del Giglio.

- Cenciaioli, L. 1991. Cunicoli di drenaggio a Perugina. Gli etruschi maestri di idraulica: 97-104.

- Cenciaioli, L. 1992. Monte Acuto (Umbertide, provincia di Perugia). Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche, 44 (1–2): 260-61.

- Cenciaioli, L. 2004. Le necropoli perugine in prossimità del Tevere. In MarcatorPlacidissimus. The Tiber Valley in Antiquity. New research in the upper and middle river valley, edited by F. Caorelli and H. Patterson. Edizioni Quasar, Roma: 387-98.

- Cenciaioli, L. 2005. Per una carta archeologica della diocesi di Perugia. In La chiesa di Perugia nel primo millennio: atti del convegno di studi, Perugia, 1-3, edited by A. Bartoli Langeli: 211-30. Spoleto, Fondazione CISAM Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo.

- Cenciaioli, L. and Sisani, S. 2009. Scavi della Cattedrale. In Invito al Museo. Percorsi, immagini, materiali del Museo Archeologico Nazionale dell’Umbria, edited byMarco Saioni: 176-180. Perugia: Fabrizio Fabbri Editore.

- Cifani, G. 2003. Storia di una frontiera. Dinamiche territoriali e gruppi etnici nella media Valle Tiberina dalla prima età del Ferro alla conquista romana. Roma: Ist. Poligrafico dello Stato.

- Cipollone, M. 1988. Gubbio (Perugia). Officina ceramica di età imperiale in loc. Vittorina. Campagna di scavo 1983. In Notizie Scavi di Antichità, 38-39, 1984-1985: 95-167.

- Cirelli, E. 2006. Classificazione e Quantificazione del Materiale Ceramico nelle Ricerche di Superficie. In Medioevo, Paesaggi e Metodi,Atti del seminario a cura di N. Mancassola, F. Saggioro, Mantova:SAP,169-178.

- Colonna, G. 1985. Santuari d’Etruria.Arezzo: Regione Toscana, Electa.

- Dareggi, G. 1972. Urne del territorio perugino, Roma: De Luca Editore.

- De Angelis, M.C., R.P. Guerzoni and Moroni, A. 2014. Il bacino del lago Trasimeno in epoca preistorica e protostorica. Collezioni storiche e indagini recenti. In Gentes, I. I:16-9.

- DeDonato, V. 1988. Le più antiche carte dell’Abbazia di S. Maria in Val di Ponte (Montelabate). Roma: Ist. Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo.

- Diosono, F. 2008. Il commercio del legname sul fiume Tevere. In MarcatorPlacidissimus. The Tiber Valley in Antiquity. New research in the upper and middle river valley, edited by F. Caorelli and H. Patterson: 251-283.Roma: Edizioni Quasar.

- Di Giuseppantonio, P., P. Guerrini and Orazi, S. 2003. Trasformazione dell’insediamento rurale nel territorio dell’Umbria: il caso delle villae. Alcune considerazioni. In XVI Congresso Internazionale di studi sull’altomedioevo, I Longobardi dei Ducati di Spoleto e Benevento, Spoleto 2003: 1377-1419.Spoleto: Fondazione CISAM Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo.

- Di Giuseppe, H. 2005. Villae, villulae e fattorie nella Media Valle del Tevere. In Roman villas around the Urbs. Interaction with landscape and environment. Proceedings of a conference held at the Swedish Institute in Rome, September 17-18, 2004, edited by F. Santillo e Klynee: 1-19. Roma: The Swedish Institute in Rome. Projects and Seminars 2.

- Di Miceli, A. 2010. Popolamento tra città e campagna nell’Umbria tardoantica. Una nuova analisi.In Aurea Umbria. Una regione dell’Impero nell’era di Costantino, Bollettino per i beni culturali dell’Umbria, edited by A. Bravi: 225-248. Viterbo: BetaGamma Editoria.

- Di Stefano, V., G. Leoni and Marchi, M.L. 2012. Il processo di romanizzazione dell’Umbria: analisi preliminare del sistema insediativo. In Bollettino di archeologia On Line, III, 2010/2: 1-46.

- Donnini, L. and Rosi Bonci, L.2008. Civitella d’Arna (Perugia, Italia) e il suo territorio carta archeologica. Oxford: BAR Publishing.

- Farinelli, R. 2007, I castelli nella Toscana delle “città deboli”. Dinamiche del popolamento e del potere rurale nella Toscana meridionale (secoli VII-XIV).Firenze: All’Insegna del Giglio.

- Feruglio, A. E. 1990. Perugia: le testimonianze di tipo villanoviano. In Gens AntiquissimaItaliae. Antichità dall’Umbria a Leningrado: 92-94. Perugia: Electa/Editori Umbri Associati.

- Fiocchi Nicolai, V. and Gelichi, S. 2001. Battisteri e chiese rurali (IV-VII secolo). In L’edificio battesimale in Italia. Aspetti e problemi, atti dell’VIII Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Cristiana (Genova, Sarzana, Albenga, Finale Ligure, Ventimiglia, 21-26 settembre 1998): 303-384. Bordighera: Istituto internazionale di studi liguri.

- Francovich, R. and Ginatempo, M. 2000. (Eds). Castelli. Storia e archeologia del potere nella Toscana medievale, Volumi I, Vol. 3. Firenze: All’insegna del Giglio.

- Gregori, L. 2006. La “memoria” geologico-geomorfologica in alcune città dell’Umbria e dintorni attraverso i materiali dell’antico edificato urbano. In Alpine and MediterraneanQuaternary, 1(2): 269-278.

- Grohmann, A. 1981. Città e territorio tra medioevo ed età moderna (Perugia secc. XIII-XVI). Perugia : Volumnia Editrice.

- Kolendo J. 1969. La frontière orientale de l’Etrurie et la localisation de l’un des domaines de Pline le Jeune. A propos d’une inscription de Novae.ArcheologiaWarsxXX: 62-68.

- Lanfredini, A. M. and Benvenuti, M. 2010. Alta Valtiberina Toscana. Preistoria e Protostoria di un territorio. Le ricerche, gli aspetti culturali, il paleoambiente, in IpoTESI di Preistoria, 3.1: 1-26.https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1974-7985/1874

- Maiarelli, A. 2006. Le più antiche carte della Cattedrale di San Lorenzo di Perugia (1010-1300), Vol. 8. Spoleto: Fondazione CISAM Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo.

- Malone, C.A.T. and. Stoddart, S.K.F1994. Territory, Time and State: The archaeological development of the Gubbio basin.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mancinelli, M.L. and Imperatori, E. 2020. Strumenti terminologici. Vocabolario aperto per la definizione dei siti archeologici (applicazione nella scheda SI – Siti archeologici, versione 3.00), ICCD, Roma.

- Mandorlo, A. 2024. Discovering and recording the archaeological features during the survey with UAV and QField: application and integration for studying the countryside surrounding Perugia, Umbria (Italy). Proceedings. Vol. 96(1), 2

- Mandorlo, A. (in press) –Comprendere alcune scelte insediative: Viewshede Cost-Surface analysisper lo studio di una porzione di territorio posto lungo l’Alta valle del Tevere, Umbria. In Landscape5. Una sintesi di elementi diacronici, Atti del Convegno Padova-Borgoricco, 23-24 maggio 2024.

- Matteini Chiari, M. and Mattacchioni L. 2008. Archeologia in quota. Lo scavo di monte Tezio. IL GRUSPIGNO, 1(1).

- Menestò, E. 1999. Il corridoio bizantino e la Via Amerina in Umbria nell’Alto Medioevo.Spoleto: Fondazione CISAM Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo.

- Montagnetti,R. and Guarino G. 2020. Da Qgis a QField: come la nuova applicazione Android sta agevolando il lavoro dell’archeologo. In FOSS4G-IT 2019, Padova 20-23 Febbraio.

- Moretti, G., A. Menelli and Batini,A. 1992. I nomi di luogo in Umbria. Progetti di ricerca, Perugia: Regione Umbria.Perugia:

- Moroni, A., F. Abati, A. Baldanza, M. Coltorti, M.C. De Angelis, S. Mancini, P. Pieruccini. 2011. L’alto e Medio Bacino del Tevere durante il Paleolitico Medio. Ipotesi di popolamento e la mobilità dei gruppi di cacciatori-raccoglitori neanderthaliani. BOLLETTINO DI ARCHEOLOGIA ONLINE, 2(2-3): 171-201.

- Negro, M., N. Whitehead, C. Malone, and S. Stoddart. 2024. Revisiting Gubbio: Settlement Patterns and Ritual from the Middle Palaeolithic to the Roman Era. In Land 2024, 13(9), 1369.https://doi.org/10.3390/land13091369

- Patterson, H., R. Witcher and Di Giuseppe, H. 2020. The changing Landscapes of Rome’s Northern Hinterland. The British School at Rome’s Tiber Valley Project. Oxford:ArcheopressPublishing Ltd.

- Pizziolo, G., L. Sarti, and Volante, N. 2009. Geografia del popolamento durante la preistoria recente nel territorio toscano: riflessioni metodologiche e casi studio. In Geografie del Popolamento. Casi di studio, metodi e teorie: 215-227. Siena: Edizioni dell’Università.

- Potter, T.W. 1979. The changing landscape of South Etruria. London: Elek.

- Ricci, E. 1935. Santa Maria di Valdiponte, Bollettino della regia deputazione di storia patria per l’Umbria, XXXIII. Perugia.

- Ricci, E. 1936. Memorie storiche di Pieve Pagliaccia e della sua consacrazione solenne il dì 2 agosto 1936, Perugia.

- Rossi, A. 1872. Una nuova tessera pagana. In Giornale di erudizione artistica, fasc. 4: 117-118.

- Saggioro, F. 2003. “Distribuzione dei materiali e definizione del sito”: processi di conoscenza e d’interpretazione dei dati di superficie altomedievali in area padana”. In III Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Medievale, edited by R. Fiorillo and P. Peduto, 2 voll., II, Salerno: 533-538.

- Scortecci, D. 1991. Riflessioni sulla cronologia del tempio perugino di San Michele arcangelo. Rivista di Archeologia Cristiana 67(2): 407-28. Roma: Pontificio Ist. Di Archeologia Cristiana.

- Sisani S. 2006. Umbria. Marche. Roma-Bari: Guide Archeologiche Laterza.

- Sisani, S. 2007. Fenomenologia della conquista. La romanizzazione dell’Umbria tra il IV sec. a.C. e la guerra sociale, Vol. 7. Edizioni Quasar.

- Sisani, S. 2009. DirimensTiberis? I confini tra Etruria e Umbria. In MarcatorPlacidissimus. The Tiber Valley in Antiquity. New research in the upper and middle river valley, edited by F. Caorelli and H. Patterson: 45-85. Roma: Edizioni Quasar.

- Spadoni, M.C, L. Cenciaioli, L. Benedetti. 2018. Regio VII etruria. Perusia – Ager Perusinus (I.G.M. 122; 130 I NE; I SE; I NO). In SupplementaItalica. Nuova serie, 30: 9-328. Roma: Edizioni Quasar.

- Stoddart, S. K. F., M. Baroni, L. Ceccarelli, G. Cifani, J. Clackson, F. Ferrara, I. della Giovampaola, F. Fulminante, T. Licence, C. Malone, L. Mattacchioni, A. Mullen, F. Nomi, E. Pettinelli, D. Redhouse and WhiteheadN. 2012. Opening the frontier: the Gubbio–Perugia frontier in the course of history, Papers of the British School at Rome, 80: 257–294.

- Stopponi, S. 2014. La media valle del Tevere fra Etruschi ed Umbri. In MarcatorPlacidissimus. The Tiber Valley in Antiquity. New research in the upper and middle river valley, edited by F. Caorelli and H. Patterson: 15-44. Roma: Edizioni Quasar.

- Terrenato, N. 2000. Campionatura, Francovich R., Manacorda D., Dizionario di archeologia,Laterza, Bari, 47.

- Ville e insediamenti 1983. (Eds). Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali. Soprintendenza Archeologica per l’Umbria, Ville e insediamenti rustici di età romana in Umbria.Perugia: Editrice umbra cooperativa.

- Vaccaro, E., S. Campana, M. Ghisleni, SordiniM. 2009. Maglie insediative della valle dell’Ombrone (GR) nel primo millennio d.C. Geografie del popolamento, casi studio, metodi e teorie, edited by G. Macchi Jànica: 285-300. Siena: Edizioni dell’Università.

- Valenti, M. 1995.Il patrimonio archeologico sommerso nel territorio senese. Esperienze e sperimentazioni dei primi anni’90 nell’attività di ricerca del Dipartimento di Archeologia e Storia delle Arti dell’Università di Siena. Acculturazione e mutamenti. Prospettive nell’Archeologia Medievale del Mediterraneo. 6 Ciclo di lezioni sulla Ricerca applicata in archeologia. Certosa diPontignano (SI)-Museo di Montelupo (FI) 1-5 marzo 1993. Vol. 38.sas: 63-106.Firenze: All’Insegna del Giglio.

- Valenti, M. 1999. Carta archeologica della provincia di Siena. Volume III. La Val d’Elsa (Colle Val d’Elsa e Poggibonsi). Siena: Nuova immagine editrice.

- Violante, C. 1982. Le strutture organizzative della cura d’anime nelle campagne dell’Italia centrosettentrionale (secoli VX).In Cristianizzazione ed organizzazione ecclesiastica delle campagne nell’alto medioevo:963-1158. Spoleto: Fondazione CISM Centro Italiano di Studi sull’alto medioevo.

- Zaccaria, C. 1994. Il territorio dei municipi e delle colonie dell’Italia nell’età alto imperiale alla luce della più recnte documentazione epigrafica. In Actesducolloque international de Rome (25-28 mars 1992).Publications de l’École Française de Rome 198.1: 309-327. Roma.

- Zanini, E. 1998. Le Italie bizantine. Territorio, insediamenti ed economia nella provincia bizantina d’Italia: V-VIII secolo. Vol. 10. Bari: Edipuglia.

-

Figure 1 - The area selected for this study in the central western sector of Umbria

Figure 1 - The area selected for this study in the central western sector of Umbria -

Figure 2 - Some examples of UAV survey: 3D models, Orthophotos, DEM and one example of anomalies’ interpretation.

Figure 2 - Some examples of UAV survey: 3D models, Orthophotos, DEM and one example of anomalies’ interpretation. -

Figure 3 - Some examples of fieldwork activities: a) the pictures above and on the right show the land visibility of the surface and the status of the materials discovered; b) geo-referencing data collection in real-time with QField and an example of 3D model from survey activities; c) Late Antique coins discovered during the survey activities

Figure 3 - Some examples of fieldwork activities: a) the pictures above and on the right show the land visibility of the surface and the status of the materials discovered; b) geo-referencing data collection in real-time with QField and an example of 3D model from survey activities; c) Late Antique coins discovered during the survey activities -

Figure 4 - Visibility maps of the examined territory: a) urban and wooded spaces are highlighted; b) survey visibility map in relation to the fields investigated between October 2020 and September/October 2021.

Figure 4 - Visibility maps of the examined territory: a) urban and wooded spaces are highlighted; b) survey visibility map in relation to the fields investigated between October 2020 and September/October 2021. -

Figure 5 - Presence of Prehistoric materials due to the geological deposits of “scaglia”.

Figure 5 - Presence of Prehistoric materials due to the geological deposits of “scaglia”. -

Figure 6 - Hellenistic-Late Republic evidence mentioned in the text and the survey data (the 3rd/2nd centuries BC - first half of the 1st century BC).

Figure 6 - Hellenistic-Late Republic evidence mentioned in the text and the survey data (the 3rd/2nd centuries BC - first half of the 1st century BC). -

Figure 7 - Heatmap of Vernice Nera.

Figure 7 - Heatmap of Vernice Nera. -

Figure 8 - Evidence in the north sector and the survey data mentioned in the text during Proto-Mid Imperial (mid-1st century BC - early 3rd century AD).

Figure 8 - Evidence in the north sector and the survey data mentioned in the text during Proto-Mid Imperial (mid-1st century BC - early 3rd century AD). -

Figure 9 - Evidence in the south sector and the survey data mentioned in the text during Proto-Mid Imperial (mid-1st century BC - early 3rd century AD).

Figure 9 - Evidence in the south sector and the survey data mentioned in the text during Proto-Mid Imperial (mid-1st century BC - early 3rd century AD). -

Figure 10 - Evidence and the survey data mentioned in the text during Late Antiquity (4th - early 6th century AD).

Figure 10 - Evidence and the survey data mentioned in the text during Late Antiquity (4th - early 6th century AD). -

Figure 11 - Evidence and survey data mentioned in the text during the Middle Ages (8th – 14th century AD).

Figure 11 - Evidence and survey data mentioned in the text during the Middle Ages (8th – 14th century AD). -

Figure 12 - Heatmap of “fondopiatto” amphorae from Imperial period.

Figure 12 - Heatmap of “fondopiatto” amphorae from Imperial period. -

Figure 13 - Heatmap of “fondopiatto” amphorae from Late Antique period.

Figure 13 - Heatmap of “fondopiatto” amphorae from Late Antique period.