Rocca Savelli (Aventine Hill). Contribution to the knowledge on defence systems for family goods in Rome during the late Middle Ages Andrea Fiorini

This paper concerns the results of the archaeological investigations at the Savelli fortress on the Aventine Hill in Rome. This fortification surrounds a well-known park of the city: the Giardino degli Aranci. The research has been addressed to improve the knowledge on a topic of great historical interest: the architectural typologies developed by Roman aristocratic families in order to defend their properties. Locating Rocca Savelli within a specific architectural typology is problematic, due to the lack of research on this site. The research team of the Department of History and Cultures of the University of Bologna has surveyed the remains, studied their building features and documented stratigraphic data. This paper summarises the preliminary results of such research effort. The structures still conserved above the ground level can be dated back to the second half of the 13th century and are the output of craftsmen specialised in building with local tuff. The fortification was most likely built by the Savelli family in order to defend its dwelling on the Aventine Hill. The next step of the research will be addressed to in-depth analyses of data collected during the fieldwork. The aim is to better specify the original features of the structure and its later modifications. At a later stage, it will be possible to understand the economic, cultural and ideological background of the people connected to the fortification (patrons, builders and inhabitants). Ultimately, the project will include geophysical prospections and small excavations across the park to investigate the presence of further structures conserved below the present ground level.

Introduction

From the 11th century, a strong demographic increase brought to a denser urban tissue. This originated in a wide architectural renewal involving infrastructures (town walls, roads, etc.) and buildings: from churches and monasteries to the palaces of religious and civil powers, to private buildings, fortresses and towers (Augenti 2020, 29-36).In this period, the wealthiest families in Rome controlled entire sectors of the city through a system of fortifications and towers. Based on various needs, different architectural solutions were put in place. Towers were chosen when it was necessary to control a single road or a series of strategic points in a wider area. For example, the Frangipane family controlled the Palatine Hill through such simple system (Augenti 2020, 28, 33; Carocci 2010; Di Carpegna Falconieri 1994; Hubert 1990).Closed defensive systems, composed of regularly disposed towers connected by walls and battlements, are more complex. An example of this is the fortification built by the Caetani family on the Appia Road, next to the mausoleum of Cecilia Metella. The structure built by the Savellis on the Aventine Hill may have been similar, although some questions must yet be clarified: did the size of the fortification change through time? Was it built in order to protect a group of previous buildings? Or was the area empty, allowing the establishing of a complex settlement, whose only remains are represented by the defensive system? And yet, were the structures inside the fortification built at a later moment? Such questions have oriented this study, although it is obvious that fully understanding this typology of fortifications will require involving a wider dataset of sites

Methodology

The data utilised in this study have been acquired applying the main methodological foundations of the architectural archaeology: analyses of masonry techniques, stratigraphic relationships between different building components, comprehension of building phases, in-depth analyses of building materials (Boato 2008; Brogiolo, Cagnana 2012; Francovich, Parenti 1988). The archaeological investigation has been based on 3D surveys of the architectural remains. After a first topographic approach with Total Station, the survey has been carried out through a Laser Scanner, following procedures already applied in other projects of the University of Bologna (Toniolo, Bergami, Silani 2019; fiorinini 2018; 2019). The topographic documentation of the Savelli Fortress has also required detailed photogrammetric surveys of all the frontages of the structure.

Results

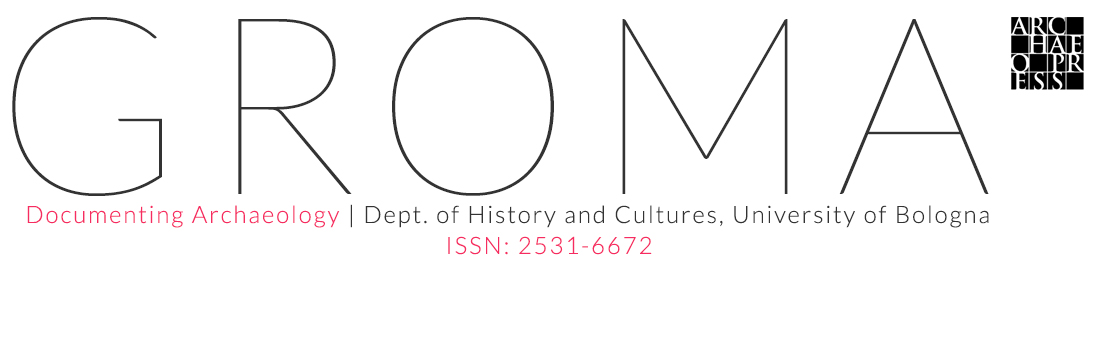

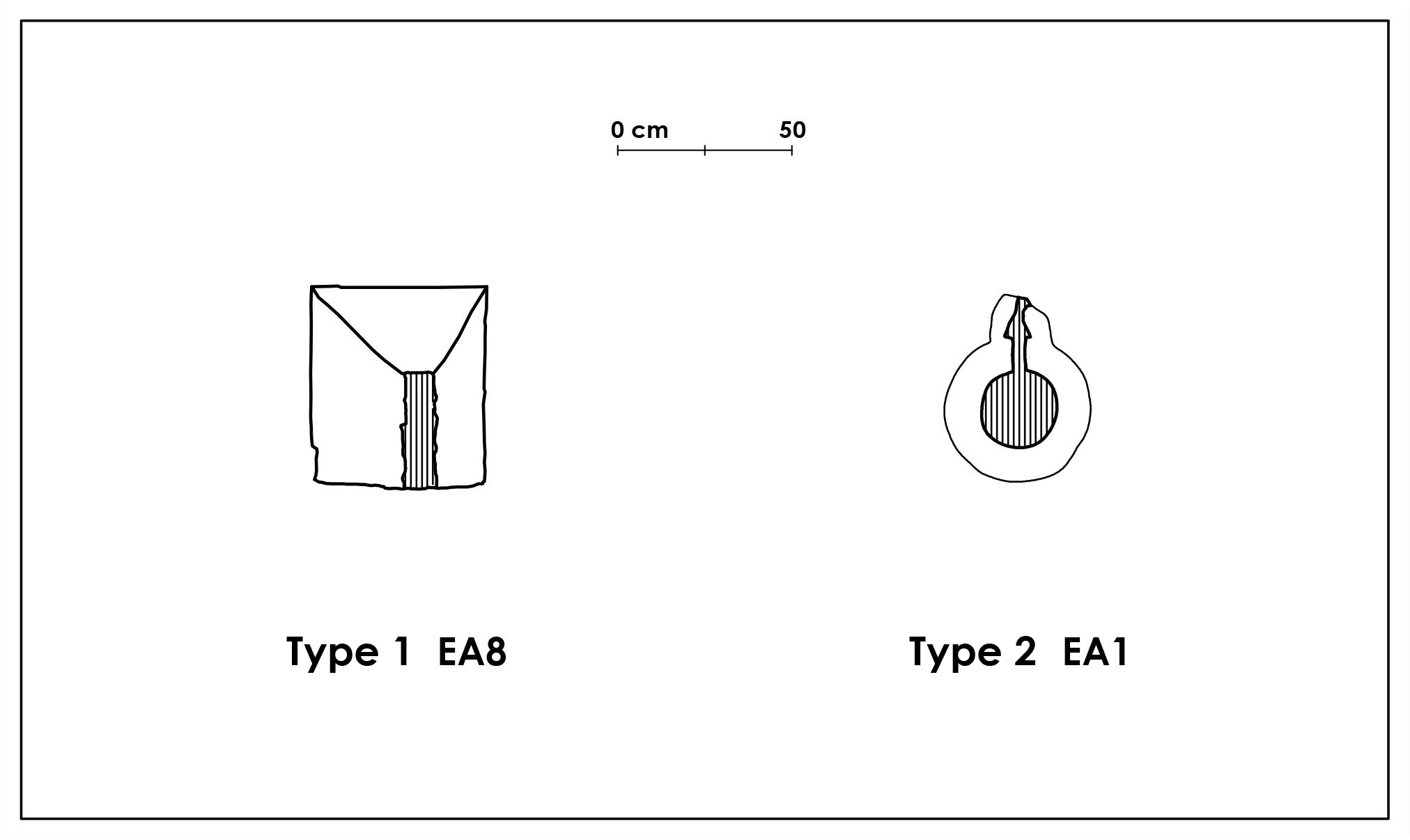

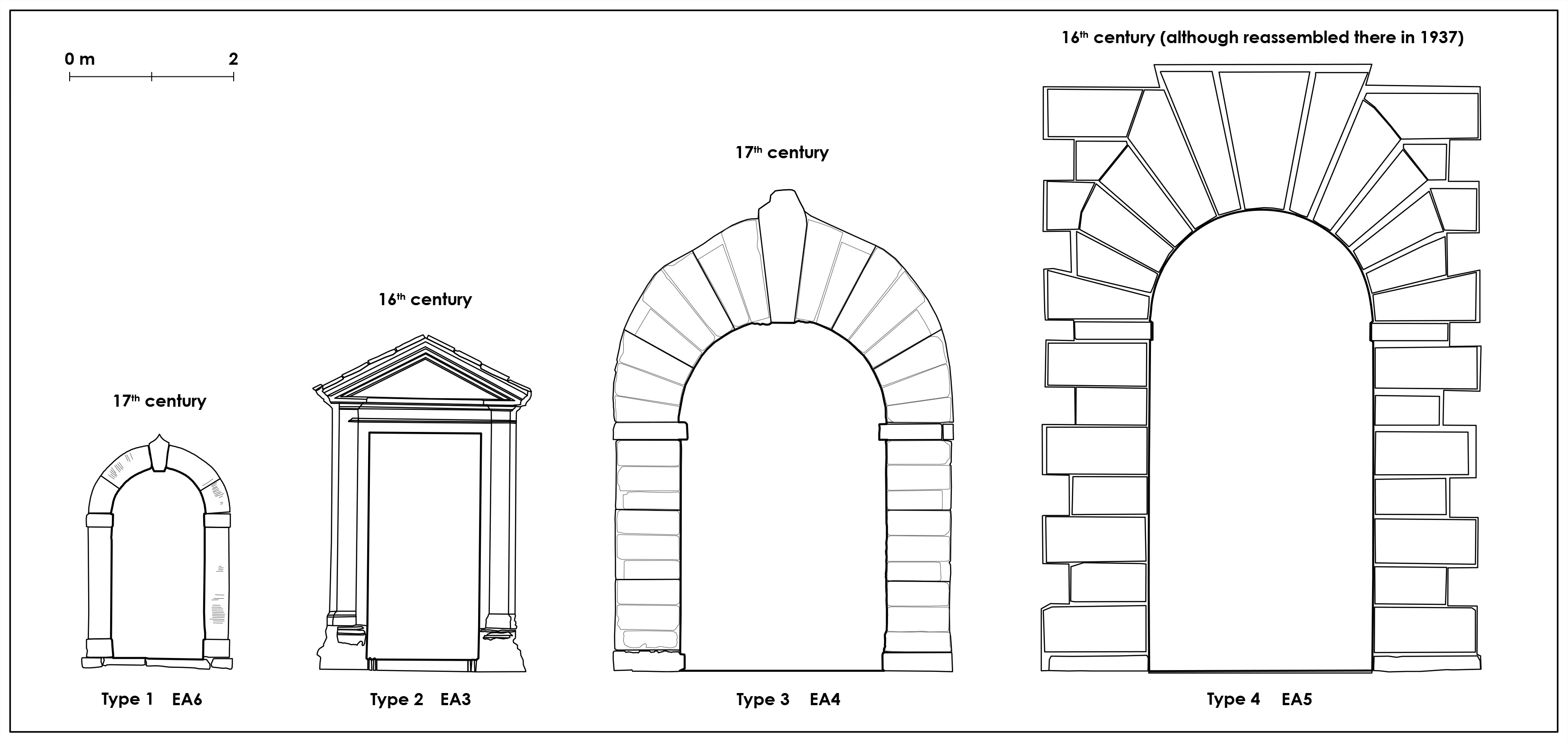

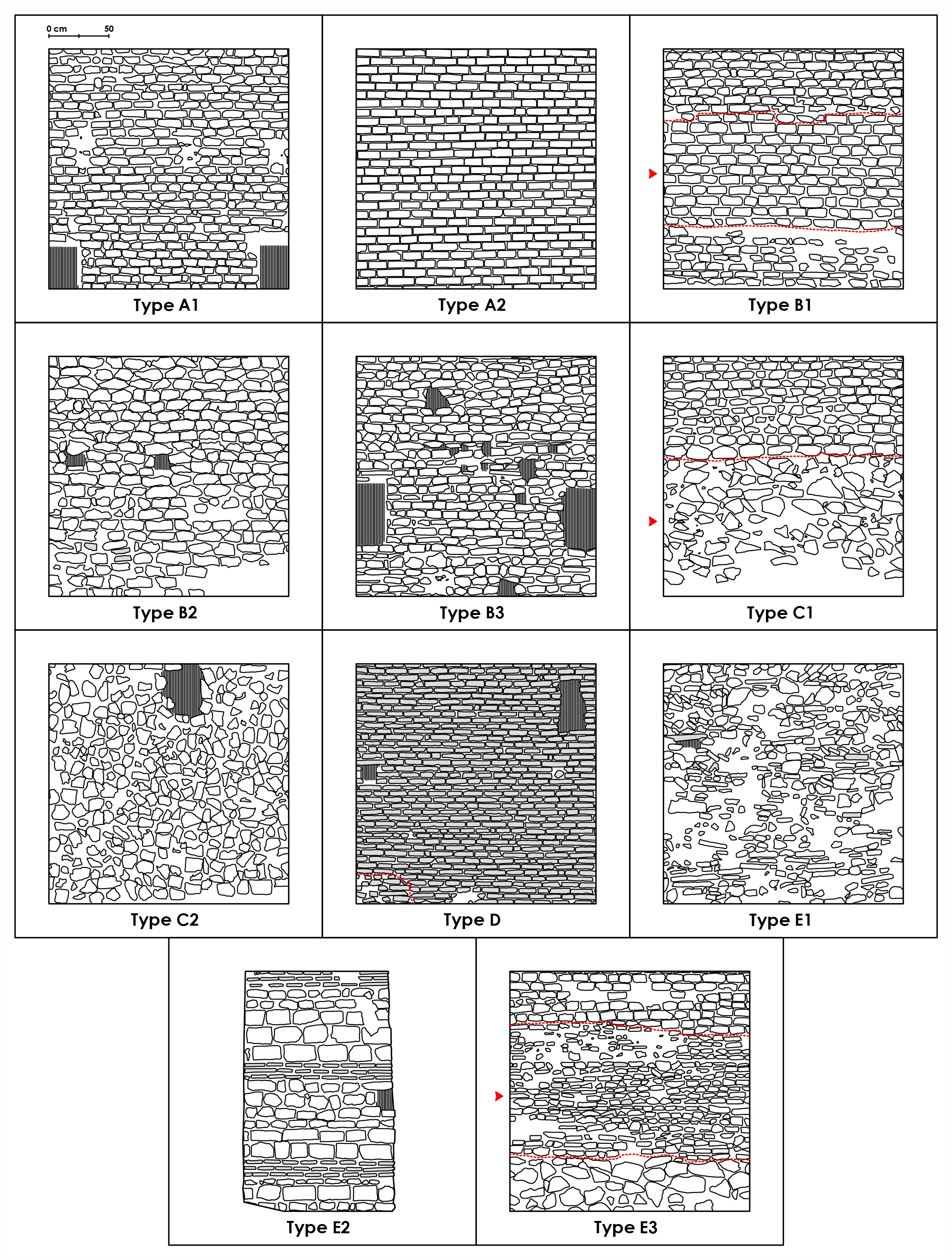

Rocca Savelli is an architectural complex featured by a squared shape (ca. 98x100 m). It is composed of six building compounds (from now on, “BC”), 38 frontages and 11 architectural elements (Fig. 1). BC1 is a gate tower projecting from the walls and belonging to the so-called “a gola aperta” typology (a kind of towers open on the inside). BC2 and 4 are towers located at the corners of the fortification, which have been consistently modified through time. BC5 is a significantly bigger structure placed in the middle of the north-west side of the fortification. The overall surface of this building (now reused as a terrace) is more than 100 m2. It most likely represented the main tower of the fortress, which allowed the visual control of a vast landscape, comprising a portion of the Tiber. BC5 is mirrored by BC3 on the opposite side of the site: a small tower placed in the middle of the walls. Ultimately, the remains of another tower can be identified on north-west corner of the fortification (BC6). Nowadays, the structure has been reused as a terrace. The area surrounded by such defensive system covers about 7,000 m2. The most ancient structures are located in the southern corner of the fortress (Figure. 1). These remains are composed of a brief portion of masonry in roughly refined tuff blocks, with no refining of the external surface. These building components are small and laid in horizontal rows. The thickness of the mortar joints varies across the masonry (Type B2). In Rome and its surroundings, these techniques (so-called ‘a bozzette tufacee’) introduced the arrival of the “regular” coursed rubblework in the 13th century. The walls in small blocks of tuff (Phase 2) are stratigraphically later than this early structure. Therefore, it is possible to propose a chronology around the first half of the 13th century for Type B2. Regarding the function of these structures, it is possible to propose two hypotheses to be verified through further archaeological investigations (GPR and excavations among them): they may either be the perimeter of a pre-existing fortification or a part of a residential complex. Furthermore, the presence of buildings next to the church of Saint Sabina would not contrast with written evidence (Figure2). As mentioned above, the southern portion of the walls of the second phase is supported by the remains of the first one. This later structure was built with a more complex technique, assembled by specialised builders. It can be unambiguously compared with 13th century structures (Fiorani 1996, 154, n. 57; Esposito 1998, 23-24, 74-75, 153-156, 311; Marta 1989, 44-46.). Building elements had been accurately refined, in terms of both shape and surface. Such small blocks are laid in horizontal rows, leaving thin mortar joints (Type A1) (Figure. 3). The presence of small sub-regular blocks instead of more irregular rubble is indicative of the high socio-economic level of the patron (Bianchi 1995). This is confirmed by the first mention of a fortress owned by the Savellis on the Aventine Hill (1279). Based on these data, the second half of the 13th century is the most suitable chronology for the foundation of the fortress (Figure. 4). By analysing stratigraphic evidence and architectural features, it has been possible to reconstruct the sequence of the building activities related to the second building phase. The patrons’ will was probably overseeing a strategic point of the city and protecting their properties: the buildings within the walls, next to the apse of Saint Sabina. Indeed, the inner surface of the fortification is perfectly plane and was most likely artificially regularised. Patrons also decided to have the fortification built with stones. The stone supply came from nearby quarries. The area where the fortress was built is mainly composed of gravels, sands and clays, therefore it must be excluded. However, a vast area stretching north-east and south-east from the fortress seems well-suited as a possible tuff quarry, as documented by geological maps (Figure. 5) 3. Consequently, utilising tuff as a building material may depend on the proximity to its quarries. At the same time, a part of the building materials utilised in the structure may have been reused from previous buildings 4 . After having found the stone deposits, stonemasons must have quarried blocks out through axes or saws. Specialised stonecutters later refined blocks in order to eliminate irregularities. There are no traces related to the refining technique usually known as anathyrosis (in Italian, ‘nastrino’=ribbon), which is typical of specialised stonecutters. However, the considerable regularity of the building components must be related to the sapient refining of highly specialised craftsmen (fiorinini 2019). Blocks does not seem to have been further refined on the side related to the surface of the wall. The tool utilised in shaping blocks was probably some kind of stonemason’s hammer, which left traces. This part of the refining process may have been performed either in the quarry or at the building place. In the first case, the operative chain was more efficient: building materials reached the building place when they were ready to be assembled in the masonry. Transport should not have been particularly difficult, since tuff is a relatively light material compared to other kinds of stone. At the same time, the area was plane and did not require pack animals. Most likely, oxen were used to drag building materials, loaded on wagons (Fiorani 1996, 87; Esposito 1998, 74). About the openings of phase 2, just a few ones have not been altered by deteriorations or later modifications. Among these architectural elements, some small windows are worthy of mention since well connected to the masonry (therefore contemporary with the fortress). These small openings were probably used to oversee the north-east moat (nowadays, Clivo di Rocca Savella) and the nearby road alongside the south-east frontage (Via di Santa Sabina). The architectural element 7 (from now on, “EA”) belongs to this typology (Figure. 6) 5. It is possible to notice several 14th century restorations (Phases 3-4), while the scarps of the BC1 gate tower were partially coated with bricks (Phase 5) (Figure. 7). The second half of the 15th century represented a crucial moment of the building history of the fortress (Phase 6). After some restorations, investments kept maintaining the structural efficiency of the fortification, also by strengthening the defence systems. In this period, the fortress was provided with a multitude of gun slits (Type 1 and 2). Indeed, these architectural elements had been built piercing the 13th century walls (Phase 2). The EA8 belongs to the first typology 6, while EA1 can be associated to the second one (Figure. 8) 7. This functional component can be compared to other architectural elements from the 15th-16th century. By analysing the medieval gun slits, it is possible to clarify the function of some openings of the fortress. The first type is featured by a “manoeuvring chamber” that narrows down to a width of 6-7 cm. Consequently, the opening was able to host weapons of no more than 60 mm calibre (the inner diameter of the barrel). Considering the height of the opening from the ground, the most suitable choice was a sort of small portable cannon, used between the 15th and the first quarter of the 16th century. It had a long barrel and it was provided with an element (crocco) or a bracket used to dock the cannon to the wall (Figure. 9). All the gates surveyed around the fortress had been built later than phase 2, since they required piercing the walls. These elements show architectural and building features clearly linked to the modern period. The monumental gate (EA5) comes from Villa Balestra (16th century) and was reassembled in Rocca Savelli in 1937. A photograph from the 1920s shows the absence of this architectural element along the walls (Figure. 10). Another modern opening (EA6, Type 1) can be found on the south-west frontage and belongs to a well-known typology in 17th century Italy. In Rome, an example of this very common type conserved at 31 Via dei Chiavari is particularly interesting. It was a gate (nowadays reused as a window), composed of jambs and arch in Peperino tuff, while the keystone and the capitals are made with travertine. This architectural element dates back to the first half of the 17th century, since an epigraph located on the capitals mentions Stefano Zanetti (the owner). He inherited the building from his uncle Antonio in December 1623 (Figure. 11). The chrono-typological repertoire of masonry techniques is composed of three main categories: masonry in building components refined with a chisel (A); masonry in roughly refined building components (B); masonry in coarse or barely refined building components (C). Two further categories are related to brickwork (D) or masonry in mixed materials (E) (Figure. 12). Each category groups together a series of masonry techniques, with differences in terms of refining, size of the building components and layout (Tab. 1). Tab. 1 – Description of the different masonry types.

Type | Description |

| A1 | Structures built with carefully refined small rectangular blocks featured by a plain surface. Blocks (commonly defined “tufelli”) are laid on thin mortar joints. These walls are the output of a building organisation where stonecutters had a preeminent role. |

| A2 | Structures built with carefully refined rectangular blocks. Blocks are reused, rusticated and small-sized. They have been regularly laid on thin mortar joints. The reuse of previous structures is demonstrated by some elements: an inhomogeneous deterioration of the surface, fractures and gross traces of pointed tools that re-worked previously refined blocks. |

| B1 | Structures built with roughly refined, rectangular blocks, lacking in refining of the surface. Blocks are small and laid in regular rows on thin mortar joints. |

| B2 | This type is similar to the ones above, although its building components are more irregular. Therefore, its mortar joints are characterised by a varying thickness. |

| B3 | Structures built with roughly refined building elements. Blocks are small, reused and with a flat surface. They are laid in regular rows, on mortar joints featured by a varying thickness. |

| C1 | Structures built with barely refined and heterogeneously-sized blocks, irregularly assembled on mortar joints with a varying thickness. The building organisation did not require the presence of a stonecutter. Walls were exclusively assembled by masons. |

| C2 | This type is similar to the one above, although its blocks are smaller. |

| D | Structures built with reused bricks, prevalently laid as stretchers and in regular rows. The layout is irregular and with thin mortar joints. These techniques seems to have pointed towards a rationalisation of the resources available, selecting and assembling reused materials. |

| E1 | Structures in mixed materials: roughly refined stone blocks and a minor presence of bricks. Blocks are small, reused and lacking in refining of their surface. They had been irregularly assembled, leaving mortar joints with varying thickness. Bricks are also reused and had been utilised in fragments. |

| E2 | Structures in mixed materials: roughly refined stone blocks and bricks. The first ones are heterogeneously-sized and had their surface roughly flattened out. They are laid in regular rows on mortar joints with varying thickness. Brick instead, are laid in bands composed of regular rows. They are mostly laid as headers, generating an irregular layout with medium mortar joints. |

| E3 | Structures in mixed materials: barely refined stone blocks and a minor presence of bricks. Blocks are reused, small and lack in refining of their surface. They are laid in irregular rows on mortar joints with varying thickness. Bricks had been reused and assembled in fragments on irregularly thick mortar joints. |

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that Rocca Savelli can be classified in the typology of the fortified enclosures: the entire perimeter of the walls was built in the same period. However, data do not allow a full understanding of the initial project. It is still necessary to clarify if the fortification hosted other contemporary buildings in its inside. Moreover, another fascinating hypothesis cannon be excluded: the fortification functioned as a defence for an earlier residential settlement located on the hill, built before the 13th century foundation. This possibility still awaits further evidence: something that encourages future investigations. Furthermore, it will be necessary to extend the focus to other aristocratic defensive structures: for example, the apparently similar Caetani castrum.

Bibliography

- Augenti, A., 2020. Prima lezione di archeologia medievale, Bari-Roma: Laterza.

- Augenti, A., 1996. Il Palatino nel Medioevo: archeologia e topografia (secoli VI-XIII), Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Acampora, L., 2017. ‘L’area di Santa Sabina all’Aventino. Nuove acquisizioni da indagini archeologiche e ricerche d’archivio’, in A. Capodiferro, L.M. Mignone and P. Quaranta (eds.), Studi e Scavi sull’Aventino 2003-2015, Roma: Quasar, 185-190

- Bianchi, G., 1995. ‘L’analisi dell’evoluzione di un sapere tecnico, per una rinnovata interpretazione dell’assetto abitativo e delle strutture edilizie del villaggio fortificato di Rocca S. Silvestro’, in R. Francovich, D. Manacorda (eds.), Acculturazione e mutamenti. Prospettive nell’archeologia medievale del Mediterraneo, Firenze: All’Insegna del Giglio, 361-396.

- Bianchi, L., 1998. Case e torri medioevali a Roma, Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Boato, A., 2008. L’archeologia in architettura. Misurazioni, stratigrafie, datazioni, restauro, Venezia: Marsilio.

- Bosman, F., 1990. ‘Una torre medievale a via Monte della Farina: ricerche topografiche e analisi della struttura’, Archeologia Medievale 17, 633-660.

- Brogiolo, G.P., A. Cagnana, 2012. Archeologia dell’architettura - metodi e interpretazioni, Firenze: All’Insegna del Giglio.

- Bruno, D., 2013. ‘Regione XIII. Aventinus’, in A. Carandini, P. Carafa (eds.), Atlante di Roma antica. Biografia e ritratti della città. 1. Testi e immagini, Milano: Electa, 388-420.

- Carocchi, S., 2010. Vassalli del papa. Potere pontificio, aristocrazie e città nello Stato della Chiesa (XII-XV sec.), Roma: Viella.

- Ciarocchi, B. and M. Ricci, 2017. ‘I materiali. Dati per l’elaborazione di un profilo storico dell’Aventino’, in A. Capodiferro, L.M. Mignone and P. Quaranta (eds.), Studi e Scavi sull’Aventino 2003-2015, Roma: Quasar, 171-184.

- Delogu, P., 1983. ‘Castelli e palazzi. La nobiltà duecentesca nel territorio laziale’, in A.M. Romanini (ed.), Roma anno 1300, Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 705-713.

- Di Carpegna Falconieri, T., 1994. ‘Torri, complessi e consorterie. Alcune riflessioni sul sistema abitativo dell'aristocrazia romana nei secoli XI e XII’, in Rivista storica del Lazio 2, 3-15.

- Docci, M., E., Chiavoni, 2017. Saper leggere l’architettura, Bari-Roma: Laterza.

- Esposito, D., 1998. Tecniche costruttive murarie medievali. Murature “a tufelli” in area romana, Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Fiorani, D., 1996. Tecniche costruttive murarie medievali: il Lazio meridionale, Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- fiorinini, A., 2019. I castelli della Romagna. Indagini di archeologia dell’architettura, Firenze: All’Insegna del Giglio.

- fiorinini, A., 2018. ‘An Urban Archeological Project in Rimini. Preliminary Report (2017-2018). The Contribution of Building Archaeology to Research and Conservation’, in Groma 3, 1-15.

- Francovich, R., R. Parenti (eds.), 1988. Archeologia e restauro dei monumenti, I Ciclo di Lezioni sulla Ricerca applicata in Archeologia (Certosa di Pontignano 1987), Firenze: All’Insegna del Giglio.

- Hubert, É., 1990. Espace urbain et habitat a Rome du X siècle à la fin du XIII siècle, Roma: Ecole française de Rome & Istituto storico italiano per il Medio Evo.

- Krautheimer, R., 1981. Roma. Profilo di una città, 312-1308, Roma: Edizioni dell’Elefante.

- Krautheimer, R., Spencer, C. and W. Frankl, 1970. Corpus Basilicarum Christianarum Romae. The Early Christian Basilicas of Rome (IV-IX Cent.), 4, Città del Vaticano: Pontificio istituto di archeologia cristiana.

- Maischberger, M., 1996. ‘Marmorata’, in E. Margareta Steinby (ed.), Topographicum Urbis Romae, 3, Roma: Quasar, 223.

- Marta, R., 1989. Tecnica costruttiva a Roma nel Medioevo, Roma: Kappa.

- MGH, Tholomei=Tholomei Lucensis Annales, 1930. MGH SS rer. Germ. N. S., VIII, Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1930.

- Reg. Hon. IV=Maurice, Prou (ed.), 1886-1888. Les registres d’Honorius IV, Paris: Ernest Thorin.

- Santangeli Valenzani, R., 2001. ‘La residenza di Ottone III sul Palatino. Un mito storiografico?’, in Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma 102, 163-68.

- Sereni, A., 2017. ‘Santa Sabina all’Aventino. La documentazione d’archivio per la ricostruzione del complesso in età medievale e moderna’, in A. Capodiferro, L.M. Mignone and P. Quaranta (eds.), Studi e Scavi sull’Aventino 2003-2015, Roma: Quasar, 191-202.

- Toniolo, L., Bergami, S. and M. Silani, 2019. ‘A new topographic survey of the walls of Pompeii: Porta Nola from 3D laser scanner to conservation problems’

Figure 1. Plan of the architectural complex and its building compounds

Figure 1. Plan of the architectural complex and its building compounds Figure 2. Plan of the architectural complex and its building phases.

Figure 2. Plan of the architectural complex and its building phases. Figure 3. South-east frontage (PR2) - detail: connection between the walls in small blocks (right) and the earlier structure in roughly refined rubble (left).

Figure 3. South-east frontage (PR2) - detail: connection between the walls in small blocks (right) and the earlier structure in roughly refined rubble (left). Figure 4. South-east frontage (PR2) – detail and main masonry types. The most ancient structures are indicated through the codes “B2” (Phase 1, first half of the 13th century) and A1 (Phase 2, second half of the 13th century).

Figure 4. South-east frontage (PR2) – detail and main masonry types. The most ancient structures are indicated through the codes “B2” (Phase 1, first half of the 13th century) and A1 (Phase 2, second half of the 13th century). Figure 5. Distribution of lithic tuff around the archaeological site (figure elaborated from the Geological Map of the Metropolitan City of Rome).

Figure 5. Distribution of lithic tuff around the archaeological site (figure elaborated from the Geological Map of the Metropolitan City of Rome). Figure 6. Opening from the second half of the 13th century (Phase 2).

Figure 6. Opening from the second half of the 13th century (Phase 2). Figure 7. The gate tower (BC1), along the north-east side of the fortress

Figure 7. The gate tower (BC1), along the north-east side of the fortress Figure 8. Openings from the second half of the 15th century (Phase 6).

Figure 8. Openings from the second half of the 15th century (Phase 6). Figure 9. Analysis of the compatibility of modern weaponry with the openings built during the second half of the 15th century (Phase 6).

Figure 9. Analysis of the compatibility of modern weaponry with the openings built during the second half of the 15th century (Phase 6). Figure 10. Doors and gates from the modern period surveyed at the fortress.

Figure 10. Doors and gates from the modern period surveyed at the fortress. Figure 11. Comparison between the gate of the fortress and a directly dated match from the City.

Figure 11. Comparison between the gate of the fortress and a directly dated match from the City. Figure 12. Chrono-typological repertoire of masonry techniques. The earliest typologies are the indicated by the following codes: B2 (Phase 1, first half of the 13th century); A1 (Phase 2, second half of the 13th century), B3 (Phase 4, second half of the 14th century), D (Phase 5, 15th century).

Figure 12. Chrono-typological repertoire of masonry techniques. The earliest typologies are the indicated by the following codes: B2 (Phase 1, first half of the 13th century); A1 (Phase 2, second half of the 13th century), B3 (Phase 4, second half of the 14th century), D (Phase 5, 15th century).